Austin A40 Sports

Round the World in Three Weeks

By Alan Hess

The Route was as follows:-

LONDON - Le Bourget - Brindisi - Milan - Beirut - Lebanon - Trans/Jordan - Syrian desert - Baghdad - Basra - Bombay - Cawnpore - Allahadbad - Calcutta - Los Angeles - Indianapolis - New York - Buffalo - Toronto - Montreal - Prestwick - Birmingham - LONDON

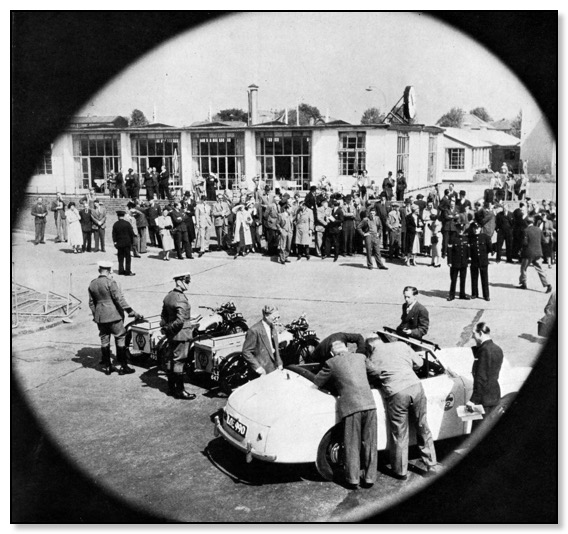

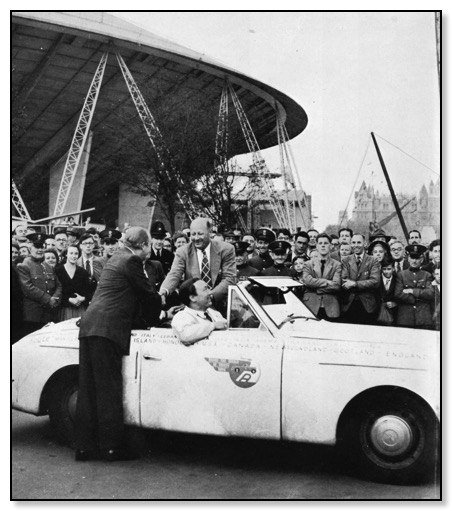

Plane's-eye view of the car, AA escort and send-off at London Airport 1st June 1951

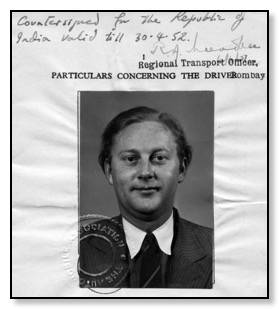

Ronald Albert Jeavons Passport

It started with a wager. In September, 1950, Leonard Lord, the chairman and managing director of the Austin Motor Company, bet me half-a-crown that I could not take an Austin round the world in a month, even by employing a plane to carry it across the oceans. This challenge led me to do some close map study, and to recall everything I knew about previous intercontinental journeys. After working out a route that avoided Russia, Malaya, and other inaccessible zones, I reported my readiness to try. Austin's set me a maximum for expenses, and explained that my chief object should be to show, with appropriate publicity, just how far and how fast an A.40 sports model could travel.

I realized that success would depend mainly on careful preparation and a suitable selection of drivers. I chose George Coates and Ronald Jeavons, both of whom had been with me on record-breaking runs in France and America. To complete the team I invited Ralph Sleigh, along with my mechanics Raleigh Appleby and Joe Galvin who would go in the plane that accompanied the car.

Ralph Sleigh

It was necessary to find a suitable aircraft, So I approached BOAC. and KLM. Royal Dutch Airlines. BOAC., to my disappointment, were not in a position to undertake the job, whereas KLM. was so enthusiastic that the choice was made for me. The Skymaster DC4 "Edam" was earmarked for the assignment, and KLM. picked a special crew of nine, placing Captain Jim Bak in charge. Then they set about designing and constructing a loading ramp of light tubular steel.

Now it was time to look at the equipment need along with working out the route and time table.

I decided to fit a white hood to reflect the sun's rays, and such special electrical devices as twin fog lamps and a plug-in inspection lamp on a long flex. Appreciating the advantages of radio-intercom between the car and the aeroplane, I approached Pye Telecommunications of Cambridge, who agreed to provide the apparatus. A screen-wide green glass sun visor was fitted, and also an additional horn-button, mounted on the floor on the passenger's side in order to leave the driver's hands free. The whole car was sprayed with a matt finish, and metal parts within the driver's vision were painted to eliminate irritating reflections. Finally a screen spray was installed to keep the windscreen clear in the mud of the Indian monsoon. Apart from these innovations, and the provision of a double-sized petrol tank, nothing was done to the car beyond running it in with meticulous care and dismantling and refitting the engine.

It seemed wise to include two spare wheels and two jerricans, one of petrol and one of water. As these heavy items, together with the radio-telephone, had to be accommodated behind the two front seats, I kept the remaining tools and spares down to the minimum consistent with safety. Two separate lists were prepared, the first of spares and equipment to be carried in the car, and the second of items that could be carried in the aeroplane. By far the most difficult task was the planning of the schedule which gave our itinerary, mileages, and arrival and departure times at every point, together with notes on all matters of importance as well as directions to keep us on our route. The job was made au the more complicated by the fact that I had to allow for continual change in local time. It was difficult to find out the exact points at which we should gain-particularly so because (in America for instance) some regions would be on Summer Time while others would not. There was also the International Date Line to reckon with.

I planned to use Shell petrol and oil on the trip. In North America, however, there are several States and Provinces in which the Shell organization did not function, so that my task was made more awkward by the delay in locating my American and Canadian refuelling facilities. It was surprising how accurate the schedule turned out to be in practice. One of my worst troubles in drawing it up had been to time the halts of our aircraft at each rendezvous in order to coincide with those of the car, and still to provide radio-intercom points where they were likely to be most needed. With our radio range was expected to exceed a hundred miles. We were astonished later to discover that on one occasion we had perfectly distinct reception when the aircraft was 160 miles away.

Transmitting licences had to be collected and wavebands allotted for each country through which the car would pass. Every country co-operated, but the USA was unable to provide us this facility, and so could not use our set between Los Angeles and the border of Ontario.

In those days of preparation, however, no country presented such problems as India. There were two main reasons. The first was that the only way to get the car across the mile wide River Sone at Dehri was by railway truck. One train runs each day at ten a.m. No matter how I amended my schedule it was impossible to get the car to Dehri before ten p.m.-and plainly we could not afford to waste twelve hours there. With the help of the Company's representative in India, Colonel Pratt, I finally overcame this difficulty. We arranged that a special engine should wait with steam up to haul a solitary wagon over the bridge the moment the Austin reached it.

Secondly, no car had ever come to India by air, and officialdom could not think how to deal with the situation. Bombay laconically reported that the authorities would require at least three days to clear the car through the Customs. At my request, the Commercial Adviser to the High Commissioner took the matter up, and eventually told me it was "hoped" (though without assurance) that there would be no difficulty. Things were still in this uncertain state when we left England.

Throughout this time the Foreign Relations Department of the Automobile Association, which had been responsible for the car carnet and other documents, gave inestimable help not least in furnishing a virtual running commentary on the condition of the Simplon Pass, which was still snowed up after a phenomenally hard winter. Three days before our departure on 1 June, the Pass was reported to be "usable, but only just so, great care being needed."

Our plans were made public at a luncheon in London on 18 April 1951. Before leaving we found ourselves appointed official Goodwill Ambassadors of the Festival of Britain, whose badge was mounted on our bonnet. Six journalists were to ride in the aeroplane. I had to refuse many requests from other people who wanted to come with us.

At exactly eleven o'clock on the morning of 1 June, 1951, the A.40 threaded its way out of London Airport, with AA. motor cycle patrols fore and aft. On the short stretch to the coast all four drivers went in the car, a procedure we intended to repeat only on our return south to Heath Row from Prestwick. Along the great arc of the journey two men at a time would be in the car, while the other two rested in the plane. Sleigh and Coates were paired off as drivers, and Jeavons and myself.

Car is put on the Aircraft for the first time.

Our route lay from London Airport to Manston, thence by air to Le Bourget, and then down through France and Switzerland to Brindisi, with a change of drivers at Milan. At Brindisi the car was to be emplaned once more and flown to Beirut, travelling overland by way of the Lebanon, Trans-Jordan and the Syrian desert to Baghdad, where another change of drivers would precede its journey down to Basra. From Basra we were all to fly to Bombay. My trans-Indian route ran north-east to Cawnpore and thence to Allahabad, where Sleigh and Coates would take over and carry on to Calcutta. The long flight from Calcutta to Los Angeles was to be undertaken in a series of easy hops. The first of these was to take us to Manila, the second to Guam, the third to Wake Island, the fourth over the International Date Line to Honolulu, and the fifth to Los Angeles. After leaving Los Angeles the car was to proceed non-stop (apart from refuelling) to Indianapolis, and thence to New York and up into Canada by way of Buffalo and Toronto. At Montreal it would again be loaded into the aircraft for its final lift across the Atlantic by way of Gander, Newfoundland, to Prestwick. From there it would travel back to its starting-point at London Airport, stopping for half-an-hour at the Austin works in Birmingham.

We started amid encouraging sunshine. An article in the previous day's Daily Express had enjoined the public to watch out for us. At Sittingbourne an entire school stood cheering beside the road, and there were frequent cries of "There they go," "There it is," and-in Chatham-"Look, there's that thing!"At Manston the Skymaster awaited us, with loading ramp ready, having taken off from Heath Row with our Press companions at the moment of our own departure by road. We lunched in the officers' mess while the car was being loaded and then, precisely on schedule, we took off and climbed into a cloudless sky.

The sky stayed clear over the Channel, but at Le Bourget rain was falling heavily and an ugly fog was beginning to gather. A crowd of friends awaited us at the French airport, and after the formalities, some Parisians announced that they would lead us in their own car from the airport out on to Route Nationale 19, which leads to the Swiss frontier at Vallorbe. I had my cherished schedule and a marked map to show me the best way to reach this road, but did not feel that I could decline the offer with out appearing churlish. Had I known that these people would lead us into the maelstrom of Paris traffic and then admit, when we all fetched up outside the Zoo, that they had lost their bearings, I would gladly have appeared not merely churlish but positively insulting.

Jeavons and I examined our map amid the gathering darkness, and, after a while, spotted the word "Zoo," whereupon we were so impolite as to climb back into our car and shoot off without a word. This incident had caused us an hour's delay, and a delay like that at the outset of a tour like was a serious matter.

All through the night we encountered torrential rain and patches of thick fog, and, try as we would, we simply could not make up for lost time under such conditions. After covering about 200 miles we pulled up to refuel at Genlis, and 105 miles farther on we reached the Swiss frontier, just as the first streaks of dawn appeared. It was obvious from the way in which the officials hurried us through that they knew of our mission and were expecting us.

Driving in the Simplon was difficult, the tight-packed snow being rendered all the more slippery by the rain which had persisted throughout the night, but as we slithered down towards Gondo the sky brightened and it looked as if a fine day were in prospect. At Iselle we crossed the frontier into Italy, again without delay, and headed for Domodossola. The lakeside road through Stresa down to Sesto-Calende was very lovely, but on that hot Sunday morning it was thronged with week-enders travelling in the opposite direction, and only when we got on to the Autostrada could we push the speed up into the seventies. At the Malpensa Airfield in Milan, Sleigh and Coates were waiting to take over and drive on to Brindisi. Jeavons and I left in the plane at six o'clock that evening. About two and a half hours later we flew low over the car near Fano, and I chatted with the drivers over our intercom, leaming that they had travelled behind a bicycle race for thirty miles before the riders turned off down a side road. By the time they reached Brindisi, however, the car was on schedule, and a couple of hours later it was in the aircraft on its way to Beirut.

At the Lebanese airport the Austin was unloaded, refuelled, and cleared by Customs so rapidly that Jeavons and I were on our way to Damascus in an hour. The first twelve miles proved to be a tough and tortuous climb to an altitude of over 4,500 feet. Afterwards the road was good, though dangerous on account of the native drivers of large American cars and over-laden buses, who could best be described as driving "with an utter disregard for their personal safety."

Dawn broke as we reached the next frontier post. The road had been a nightmare. It consisted of a series of shattering pot-holes which one could not see in time to avoid. We expected to break a spring or a shock-absorber every minute. All we did break was the glass water-reservoir of our screen spray, which we replaced with a metal one on arrival at LosAngeles.

Within a couple of hours of sunrise the sun became intolerably hot, as we travelled with our windows shut to protect ourselves from the fiery air outside. Even under these conditions we managed to kept ahead of schedule, although we were running out of drinks. Between Rutba and our refuelling point at Ramadi I made contact with the aircraft and explained how things were with us, whereuponBak said he would drop a jerrican of drinking water by parachute.

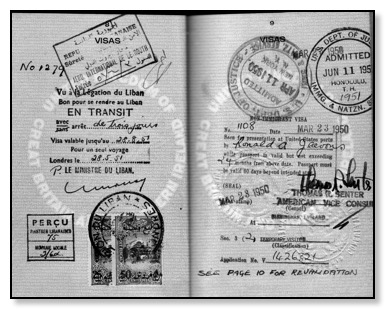

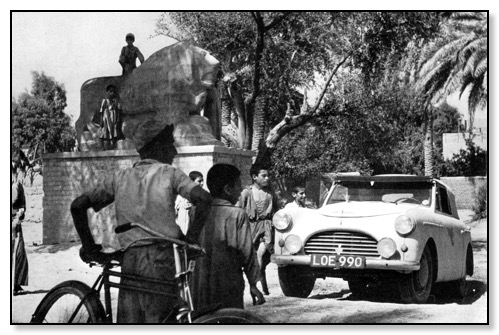

In Baghdad - the monumental lion is said to have been excavated

on the site of the original Babylonia temple

He was then 160 miles to the north-west, so we gave him a map reference for our whereabouts and pulled up. Before the radio conversation ended I said I believed we should arrive in Baghdad eleven hours ahead of schedule, and that because of the dust it would be prudent to use some of this time in changing the engine oil and cleaning the air filters. Waiting in the blistering heat, the bodywork of the car too hot to touch, it seemed ages before we heard a distant drone. A couple of minutes later we saw the plane flying at about 4,000 feet straight behind us and approximately over Rutba. The crew contacted us, and asked me for an estimate of the ground velocity of the wind and its direction. I guessed the velocity to be about 20 m.p.h., whereupon the plane circled widely, and after a while the parachute unfurled and sailed down, carrying the jerrican right over our heads to land a quarter of a mile away. I thought this was quite accurate, but the aircrew were dissatisfied,and in the subsequent discussion we discovered that while they had been circling into position the wind velocity had almost doubled at ground level.

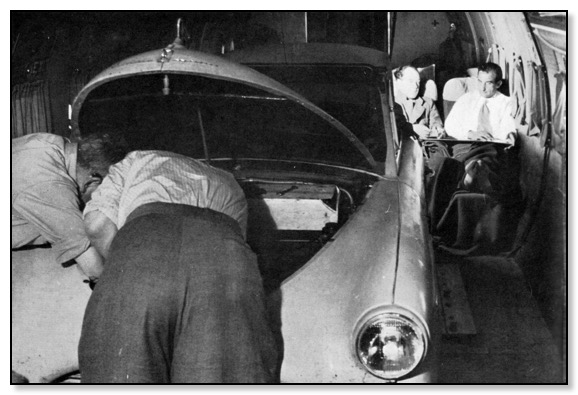

The mechanics giving the Austin a check-over in the plane.

The water refreshed us greatly, but the remaining miles into Ramadi, with deep ruts intersecting our path every few yards and the inside of the car full of choking sand, provided a drive which I should hate to repeat. At Baghdad airport we found the mechanics ready to service the car in accordance with my suggestions over the intercom, and in a very few minutes we were driven off to our hotel to take a cold shower and change our clothes.

Sleigh and Coates set off shortly after midnight, and had a trying run over roads pitted with pot holes and flooded at two points. They followed the line of the Tigris all the wayThey were hampered by dust and the gradually increasing temperature, which stood at 160º F at Basra. On the nine hours' flight from Basra to Bombay most of us managed to get some sleep. I had looked forward with apprehension to the Customs formalities awaiting us in India, but so much pressure had been applied by London and Delhi that we were hustled through with almost unseemly haste, and Jeavons and I left Santa Cruz airport at 8.30 am., dead on time.

We were both exceedingly tired and finding it difficult to keep awake, yet still I grew drowsy. Only the alertness of Jeavons, who should have been resting, saved us from disaster. He seized the wheel just as I was nodding off. We changed places, and about twenty minutes later I was feeling rested, I assured him I had recovered so we changed back again. Half-a-dozen times that night the same thing happened. I found I simply could not stay awake. Poor Jeavons must have spent a bad night; I did not enjoy it much myself. At last, early the following morning, we arrived at Jhansi. There we were to collect petrol coupons to enable us to refuel at Cawnpore, where petrol is rationed.

By the time we restarted if was fully light, and we set out in good spirits on the 108 miles to Cawnpore, to be followed by another 130 miles to Allahabad. The most exciting part of this stretch was the crossing of the River Jumna just beyond Kalpi, where one has the choice of using the occasional ferry or sliding down a sandbank and hoping to arrive at the bottom with the car pointing in the right direction to get on to the narrow pontoon bridge at the foot. I chose the sandbank method. All went well, and we clattered on the seemingly interminable bridge, to find ourselves confronted on the far side by another sandbank almost totally blocked by bullocks and stranded vehicles. We stormed it at high speed, hoping for the best. Panic-stricken natives leapt out of our way at the last second. Wandering goats and dogs escaped by inches, but we got over the crest of the dune and carried on.

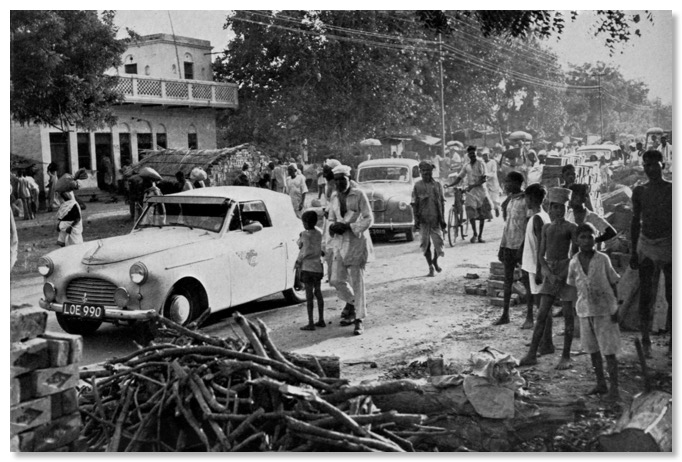

Street scene in Allahabad - typical of the congestion in Indian towns.

We covered the 933 miles from Bombay to Bamrante Airfield, Allahabad, at the respect-able average of 37 mph., despite repeated instances of being forced off the road into the soft dirt by native bus and lorry drivers, and despite the stubborn refusal of bullock carts to make room for us to get past. At Allahabad we were more than three days ahead of schedule. Sleigh and Coates set out immediately to finish the journey to Calcutta, in the course of which came that critical river crossing at Dehri.

The plane took off at 2.45 on the morning of 8 June. Two hours later I was in radio-telephone communication with the others. They had crossed the river safely and were now close to Asansol. The night had not been uneventful for them, however, as they had found the heat so insufferable that they had been forced to lower the hood and put up with the everlasting dust. As some protection against this they had tried to wear goggles, but these filled with sweat and became misty. Later on, a nail from a bullock shoe caused the only puncture of the whole trip, but after a short run with the spare wheel the original tyre was repaired and remounted. Still, he brought the car into Calcutta at 9 am. on 8 June 1951, having covered the 520 miles from Allahabad in fourteen and a half hours.

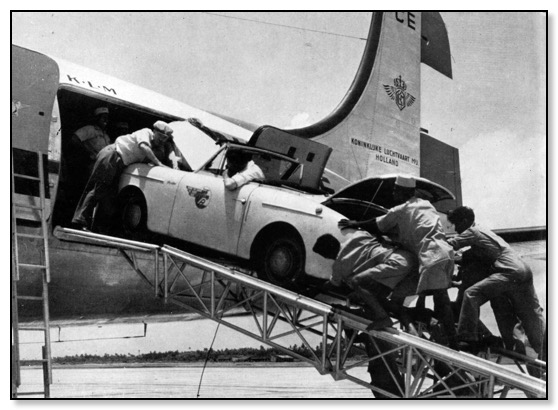

Farewell to India. The Austin goes aboard it's "flying garage"

to start the pacific crossing

We all took off at 5.30 the following morning, and when we were airborne and India was left behind us we felt that the rest would be easy by comparison. Henceforth, wherever we might stop to speak to anyone, they would understand us and we would probably under-stand them, and there was also the assurance that we should be able to get food and drink-clean food and safe drink-wherever we desired. By now we were sick to death of sandwiches and thermos flasks, and looked forward to at least one decent meal each day.

It was dark when we reached Manila. We were spellbound by the beauty of it from the air.The city was much larger than we had expected, and was twinkling with lights of every imaginable colour. Even the widely-travelled aircrew were obviously impressed so much so that when we took off again after a short stop for refuelling, Bak circled the city twice so that we could gaze once more on its loveliness.

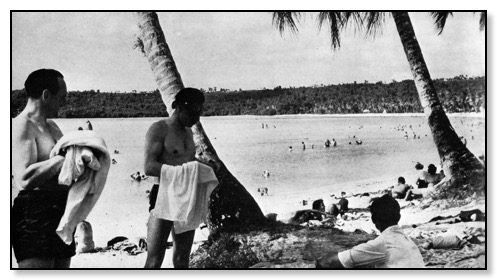

From Manila to Guam was an eight hours' hop, and we arrived at the Agana Airfield on the evening of 9 June. The island bore surprisingly few traces of the part it had played in the WWII. Great stretches of it, however, were out of bounds to civilians, and it was still administered by the U.S. armed forces. Our plane crew, under International Air Regulations, had to rest for a prescribed number of hours after a specific flying time. Consequently we were grounded on Guam for a whole day, and had to make the best of our enforced inactivity. That afternoon we all went swimming, and found the sea almost too warm to be pleasant.

Interlude at Guam

Our next hop took us to Wake, where the scene was very different. The remnants of crashed Japanese aircraft littered the minute island, and in one bay the bows of a wrecked ship reared almost vertically above the water. As we were due to pause for an hour and forty minutes while the plane refuelled, we went to the official canteen of the Naval Air personnel,who seemed to be the only inhabitants. This shack was dignified by a neon sign which pro-claimed it to be the "Drifters Reef." Inside, fifty or sixty seaman were sprawling about in various stages of undress, writing letters, playing cards, or listening with far-away expressions to the juke box. Others were swimming in a pool below the veranda at the back.

From Wake to Honolulu was 2,000 nautical miles, and we had allowed eleven hours for the flight. On this stretch we crossed the International Date Line.

We all looked forward to our first encounter with the Hawaiian paradise and to being greeted by Hula girls, who would welcome us with song. In such a glow of expectancy we disembarked. Instead of the Hula girls we were met by several surly officials whose greeting was far from flowery and whose methods were anything but tuneful. It did not take us long to find out why 11th June is a public holiday in Honolulu. Our plane was the only aircraft expected, and these Immigration and Customs men had been deprived of their vacation to deal with us, but deal with us they did. With aircrew and press guests we numbered twenty-two, and each of us was made to turn out every bag he had, while the Immigration officials raised frightening difficulties over slight discrepancies in our visas. We had landed at six o'clock in the morning. It was nine o'clock before formalities were completed but we had to leave the car in the plane, as there was no official available who could authorize us to land it.

Outside that repulsive Customs shed the authentic Honolulu met us. We were garlanded and kissed and sung to and danced to, and generally made welcome by a host of inhabitants.The person responsible for International Air Regulations was indeed our benefactor. The twenty-one hours we spent at Honolulu were sheer bliss, and we received limitless kindness.The take-off at three am. on the 12th brought us back to reality. Since leaving Calcutta we had been grounded for more than forty-six hours-time we would rather have spent behind the wheel. But the delays had been necessary, and it was good that they had been so enjoyable.

Our landing at Los Angeles must have been quite impressive. Several hundred people awaited us, not only consular officials and press and newsreel men, but an excited miscellaneous crowd. While the car was landed and refuelled, the public address system recounted the object of our journey and such adventures as had so far befallen us.

By the time we were free to leave the airport it was nearly 8 p.m. Jeavons and I were due to set out on our long drive east five hours later, with no prospect of relief, since neither Sleigh nor Coates held an American driving licence. But first, to comply with arrangements which had been made in our honour I piloted the car right into the Crystal Ballroom of the Beverly Hills Hotel, where all the motoring journalists on the west coast were assembled to meet us, together with the British Consul and the Mayor of Los Angeles.

At one o'clock in the morning a small crowd surrounded our car. Flash bulbs popped as we started off again. By the time we reached our first refuelling point at Blythe, it was daylight, and we had covered 150 miles. The desert of Arizona came as a pleasant surprise, for we had an excellent road practically A1 all the way, with none of the hazards which had hampered us during our Syrian crossing. We could not understand how the Americans dared to call this a desert. Admittedly there was little or nothing on each side of the metalled highway, but we found it possible to keep up a high average speed. We stopped to refuel at Flagstaff and again at Albuquerque, and covered 1,083 miles in the first twenty-four hours. Our most startling experience occurred near Logan, between Tucumcari and Dalbart, shortly after midnight, when we ran into a cloud of moths. In an instant the windscreen and lamps were so thickly plastered with their corpses that we could not see the road, and we had to stop and scrape them off the glass. This happened half-a-dozen times in just ten miles.

All the way to Nevada we never needed to add any oil or water, and the car was bowling along at a steady 65 m.p.h. so that we were gaining all the way on our schedule, which had provided, optimistically as I thought, for an average of 44 m.p.h. That night we both began to feel we wanted some rest, but by now we were so far ahead of time that we could envisage an altogether new ambition, that of completing our world tour within three weeks. Spurred on by this hope, we determined to stick to our original plan and run straight through to Indianapolis.

From St. Louis through Vandalia to Terre Haute we travelled 166 miles by night. The road was in a very bad state after the ravages of a severe winter, and was made all the more trying by innumerable gigantic trucks and buses, traveling at high speeds in swirls of dust.

This was the worst part of the trans-American journey. Nevertheless, we reached Indianapolis at six o'clock on the morning of 15 June, five and a half hours earlier than we had expected. Wilbur Shaw, the President of the Speedway, gave a press luncheon for us at the Athletic Club on 16 June, after which we ran the car down to the Speedway to give "the boys" a chance to look it over.

Between our arrival in Indianapolis and this occasion I had our route painted both sides of the car, and this added considerably to the interest of bystanders. By now, too,the matt cream surface had become considerably disfigured, for whenever the car was left unattended we came back to find new autographs adorning it. Most of these signatures had been inscribed in Los Angeles. The only ones we really prized were those of the BritishConsul, the Mayor of Los Angeles, and Ralph de Palma, once the world's most famous driver. Wilbur Shaw now added his.

We left Indianapolis at 5.30 p.m. on the 16th, and when we arrived at Cambridge, about midnight, we found that owing to road repairs we could not keep on Route 22 as we had planned, but had to deviate along Route 40 to Washington, Pennsylvania, and thence byRoute 19 north to Pittsburgh. Here we were accorded a tremendous reception by the Austin dealer. He had engaged a police escort to guide us out of the city to the start of thePennsylvania Turnpike. This was our first experience of following an American police escort,and we thought it at once stimulating, amusing, and frightening. It was stimulating to flash across traffic signals set against one with the protection of the law; amusing to see the way in which the local citizens drew in to the kerb, stopped, and turned off their lights; and frightening because the motor-cycle police went full tilt over incredibly bumpy surfaces standing up on their footrests. We had to follow almost flat out, hoping our springs would take it.

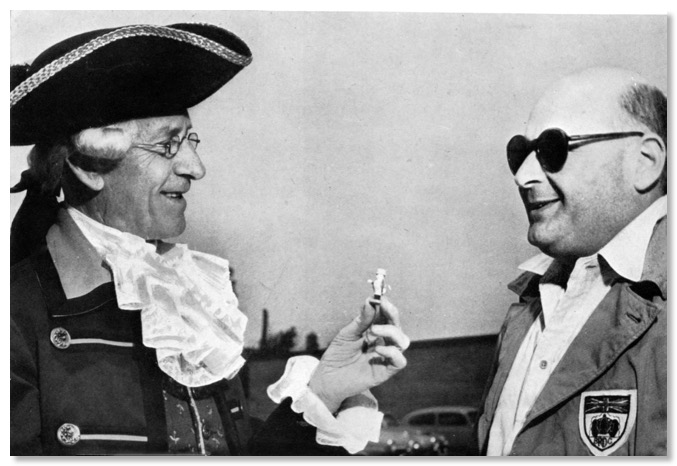

Father Knickerbocker the traditional welcomer of visitors to New York

Presented Hess with their mascot - a tiny effigy of John Bull.

In New York ( now reached a week ahead of schedule) we had a second police escort, and were hustled along in the wake of wailing sirens to be greeted at the entrance to the Holland Tunnel by "Father Knickerbocker" whose official duty it is to receive notable visitors to the city. Remembering that we came as Goodwill Ambassadors of the Festival of Britain, and that we had plenty of time in hand, I decided to stop over in New York and Toronto to comply with requests for press conferences and television and broadcast interviews. We met the plane and crew at Idlewild Airport, and then drove the car into the centre of New York and parked it in a reserved space outside the Waldorf Astoria, where it attracted great interest.

We left the Rockefeller Plaza at 3.30pm the following afternoon. The crowd was so thick that it almost prevented us from moving at all. Our next stop was to be at Coming, 263 miles on our road to Buffalo, from which the Rainbow Bridge leads over the Niagara Falls on toCanadian soil. Apart from a momentary brush with the police at Scranton, where our speed was deemed excessive and we received a homily which, to judge from its manner of delivery,had often been recited before, this part of the trip was uneventful enough, until, at 10.30pm., we were drawing out of Elmira. At this point we passed another car whose sole occupant was apparently unhappy at being overtaken. Henceforth he played cat and mouse with us, first coming up in a wild rush and sweeping past, then loitering and either letting us go to the front or, to our greater embarrassment, running alongside us trying to read the inscription on the car. This went on for seventeen miles until, just before Corning, he drew alongside for the last time and leant over to shout, "Good luck, boys! But watch out for the cops! Follow me!" So saying he mounted the high kerb and swung broadside across our bonnet, so that I nearly rammed him.

After refuelling at Corning we had some difficulty in finding the road, which was badly signposted, but our luck held and at every doubtful point we guessed right. We arrived at East Aurora, 114 miles away, two and a quarter hours later. Here we had arranged to meetAl Morriss of the Dunlop Rubber Company in Buffalo. I had discovered the year before what a confusing place Buffalo can be to strangers, and I wanted a guide through the dark-ness to the Rainbow Bridge. When we got to our meeting place I saw that he had provided a Sheriff's escort in a police car. The next eighteen miles from East Aurora to the border were, I think, the most magnificent of our whole tour. With siren screeching in the empty night the policeman kept his foot hard down. Our speed never dropped below 65 m.p.h.,and was generally around the seventies. Morris, bringing up the rear, was hard put to it to keep up with us.

The Customs and Immigration officials had clearly been warned, and the transit intoCanada took only five minutes. We actually had an hour and a half to waste before we dared enter Toronto, where a carefully prepared programme awaited us. After our reception,including what seemed like thousands of photographs, we moved off to the Royal York Hotel for what was described on the souvenir menu as an "Olde English Breakfast" with the press-immense amounts of kidneys and bacon. After breakfast I slipped off to my room to try to get some sleep-only to find a CBC. interviewer with mobile recorder awaiting me.

Our departure for Montreal the next morning coincided with rain and thunder which accompanied us most of the way to Brockville, a little over 200 miles away. From our official reception in Montreal to Dorval Airport, thence by plane to Gander, and so across theAtlantic to Prestwick, no obstacle remained. At Manston, three weeks before, I had left behind the rear seat and squab, knowing that they would not be needed again until the run south from Prestwick to Heath Row, as this was the only other occasion on which the four of us would be riding together. These awaited us at the Scottish airport and were quickly refitted.

We got away from Prestwick punctually, and drove through a rainstorm to the Austin works in Birmingham. It had been agreed that representative bodies of workers from each section of the plant should be given time off to greet the car. When Jeavons drove through the gates we were hailed by them as they waited in the rain to congratulate the car and its crew.

We left on the last hundred miles back to our starting-point with George Coates proudly at the wheel. A little over two hours later, at the Slough end of the Colnbrook By-Pass, we were met by the same two AA. outriders who had escorted us out of Heath Row three weeks earlier and were now detailed to lead us in. Here we made radio contact with the plane crew in order to synchronize our return with theirs. On the stroke of noon on 22 June, the Sky-master taxied to a standstill, and at the same second that its wheels ceased to revolve the car halted beside it on the tarmac.

This last example of accurate timing seemed to symbolize the precision with which the whole operation had been conducted. An enormous crowd had assembled to greet us, and Leonard Lord lost no time in presenting me ceremoniously with his personal cheque for half-a-crown. Two hours later our now familiar AA. outriders attended us on our way from London Airport to the South Bank Festival Site, where we were received by Sir GeraldBarry, and where, incidentally, the Austin was the only car other than the King's ever allowed to enter. In the shadow of the Dome of Discovery Sir Gerald thanked us for the job we had done as World Ambassadors for the Festival and presented me with a souvenir of the occasion. From the Festival Site we proceeded to the Mansion House, where the LordMayor accorded us the honour of a civic reception.

Alan Hess and Leonard Lord

From start to finish we had never had one moment's mechanical trouble. Our speedo-meter showed that we had driven 9,263 miles-an average of 441 miles daily. The petrol consumption had averaged just on 29 m.p.g., while the oil consumption worked out at the extraordinary figure of something over 5,000 m.p.g. Apart from the short distance on the spare tyre after the solitary puncture, we had completed the whole journey on one set of Dunlops, and we were still using the same four Champion sparking plugs with which we had started.

We, by exploiting to the full the resources of aviation and automotive engineering, had welded together a score of earlier records. All the links of the chain hung together, and had circled the planet in just three weeks.

Sir Gerald Barry, Director General of the Festival of Britain

Welcoming the team home.

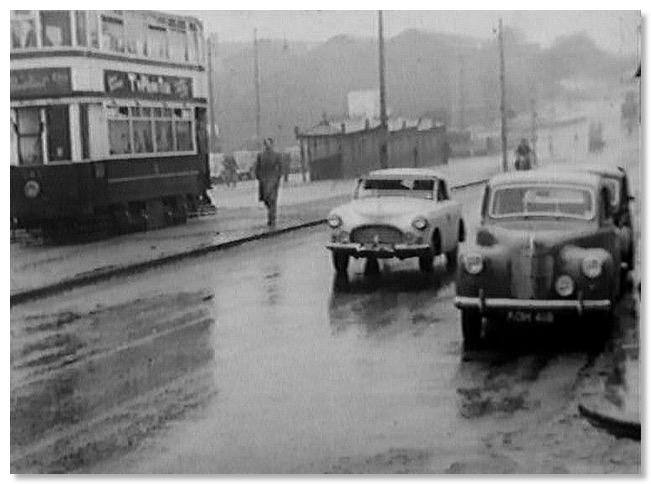

Back Home to Longbridge Lickey Road