Ricardo Burzi

Ricardo Burzi was one of the most good humoured and personable executives ever to tread the corridors of Longbridge’s administrative block. But there was much more to Dick Burzi than a naturalized Italian who looked a little like a rather squat version of the world champion racing driver, Juan Manuel Fangio.

Burzi was an inspired stylist. His talent was stunted for many years by his patron, Herbert Austin, but, under the auspices of Leonard Lord, came to full flower, only to wilt again in the hothouse intensity of fellow Italian Pinin Farina’s creative genius.

Burzi was born, no one seems quite sure when, but certainly around the turn of the last century, in Buenos Aires. His mother was French. Little is known of his Argentinian father. However, by the late 1920s he had moved to Italy and achieved the considerable kudos of working as a designer for Vincezo Lancia in Turin. He would have been there for the convention shattering Lambda, the world’s first monocoque car that was also a pioneer of independent front suspension. We don’t know whether Burzi had a hand in drafting its ‘tub-like’ body, but if he did, the style was more functional than fluid!

Rather like Leonard Lord departing Morris in 1936, the reason why Burzi left Lancia is unclear.

The colourful explanation is, that with Benito Mussolini’s fascist Nationalist Party gathering strength in Italy from 1922 onwards, Burzi, who obviously did not approve, failed to restrain his artist’s hand and very unwisely penned some uncomplimentary cartoons of le Duce for a newspaper.

Time to move on.

Vincenzo Lancia transferred him to his company’s Paris office then, by coincidence, met Austin – some sources say on the ocean liner Queen Mary, which, of course, was not even built until some years later - and recommended the acquisition of his compatriot. Or, maybe, sought to off-load someone who was potentially a political embarrassment.

A much more realistic scenario is that Austin saw examples of Burzi’s work at either the Paris Salon or London Motor Show and ‘head hunted’ him.

Whatever the truth, Ricardo Burzi arrived at Longbridge, speaking no English, right at the end of the Vintage era and instantly, and thereafter, became known as ‘Dicki’; or just ‘Dick’.

It’s said that one of his first jobs was to style the Sixteen but Sir Herbert disapproved of the result and its lack of bedrock Austin conservatism . Not a good start, but the story doesn’t make much sense. The first Austin Sixteen was launched in 1928 – a year before the Italian arrived in Birmingham. And it’s hardly likely a ‘re-style’ would have been required that early in the life of the model.

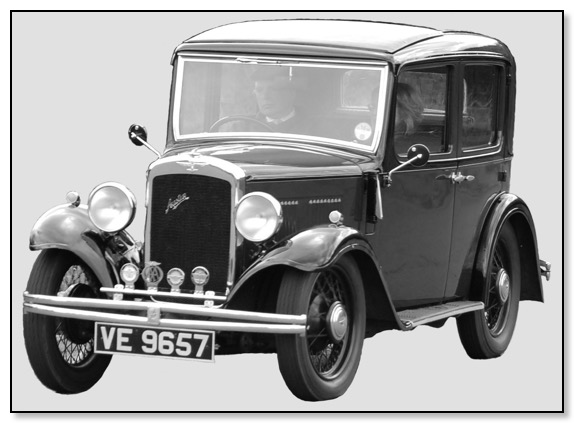

Austin Ten-Four

It’s more likely Burzi’s first major project was the Ten-Four unveiled in 1932. This is a delightful looking car. Curvaceous, within the terms of the day and beautifully balanced. It was supplemented by the mechanically suspect, but even better looking, Light Twelve Six Harley and also a Sixteen.

It was now that the dead hand of Austin began to cramp Burzi’s style. The man who believed even a mildly sloping windscreen caused eye strain and that his company should make ‘a bold stand against the fetish of change for change’s sake’ was hardly going to condone flamboyance at the drawing board.

When it came time to refresh the 10-4, in 1934, Burzi, remarkably, got away with concealing the spare wheel in a hump on the back panel, the radiator behind a slightly inclined cowl and with softening the angularity. The Twelve followed suit, now called the Ascot. The Sixteen was similarly revamped as a Hertford (York on a longer wheelbase).

The American influence on the styling of all these cars was very evident. There were hints of Ford Model A in the Austin 10-4. And Al Capone would have been as at home toting a Tommy gun from the running board of an Austin Sixteen as he would have from a Cadillac, although he would have had a better chance of dodging the cops in the American than he would the Longbridge make!

Burzi’s talent was being frustrated; but not for long. The story is almost certainly apocryphal, but by 1936 there were stirrings regarding the old-fashioned appearance of Austins and Burzi took the initiative to craft something better looking when Austin took a rare holiday. When the boss returned it was Austin himself who suggested to the designer he might modernize the styles slightly. The same afternoon Burzi produced drawings for what we know as the New Ascot Twelve.

New Ascot Twelve

Austin would not have been duped into thinking Burzi could work that quickly to produce one of the best looking popular saloons of the late 1930s, but he let the surreptitiousness pass. There was soon a Ten, Fourteen that was almost identical to the Twelve, no Sixteen, but an Eighteen that, with its stumpy bonnet, was not to every taste, and a magnificent marketing disaster in the form of a 28 horse-power limousine called Ranelagh.

The models were Burzi’s last under the restraining hand of Herbert Austin. He had captured the Longbridge ethos perfectly. The shapes were tasteful; the height of solid middle class respectability, yet with a dash of understated modernity that placed them ahead of most of the competition. Cars for the discerning, experienced motorist whose driving would be as conservative as his or her politics.

It was when these archetypal Austins were at their peak that Leonard Lord arrived on the scene as works director. Lord had several missions that spring of 1938. To put his considerable dynamic weight behind aircraft production from Longbridge’s shadow factory; to organize the Works to produce the colossal amount of other military material manufactured in WWll ; race into production commercial vehicles that turned out to be eminently suitable for armed forces use, and initiate a range of cars that would assure the company a dominant position in the private car sector.

Pleasing to the eye as Burzi’s current range was, the engineering was moribund. Overhead valve engines were now the order of the day and the first tentative steps towards chassis-less construction were being taken by other makers.

After leaving Morris Lord had undertaken a fact finding visit to America. Also, around this time, his choice of personal transport was a Series 60 Buick. There can be little doubt that when he set Burzi to work on a line-up of cars for 1939 transatlantic influences were very much in his mind, and from what we have seen already, can conclude that his designer was receptive to those ideas.

The ‘Lord-Look’ cars – Eight, Ten and Twelve – with their alligator bonnets, centre-pillar-hinged doors and ‘smiley Buick’ grilles, were modern, smart and highly appealing. The American influence, was, of course, there. But Burzi had been brilliantly subdued and the interpretation for Austin was nigh on perfect. The Eight and Ten even made an important move to ‘chassis-less’, although overhead valves had to wait.

Leonard Lord and Dick Burzi were a winning partnership. The marriage of two minds. It is inevitable we ask what was the true relationship between the firey, dynamic, sometimes ruthless, genius and the easy-going Italian, absorbed in cultivating those gently curving automobile forms.

It has been glibly remarked that Lord liked Burzi because he did what he was told. Of course, he did. Lord was the boss and Burzi was there to serve. Yet the chairman genuinely liked the Italian. When he was amongst a total of 8000 British residents who were interned as enemy aliens in WWll it was Leonard Lord, in an act of compassion and humanity, who pulled strings to have him released from ‘imprisonment’ on the Isle of Man, when the last thing Longbridge needed was a stylist.

Promising though the Lord-Look cars had been, it was in the dollar-crazed late 1940s that Burzi flowered. The A40 Devons and Dorsets were Britain’s first all-new post-War family car. The charming appearance managed to combine subtle Stateside with Austin’s world-class standards. This was work from a different school than bulbous monstrosities like, say, the contemporary Standard that tried, unsuccessfully, to capture an American flavour, or the many models that were merely mildly revamped pre-War styles.

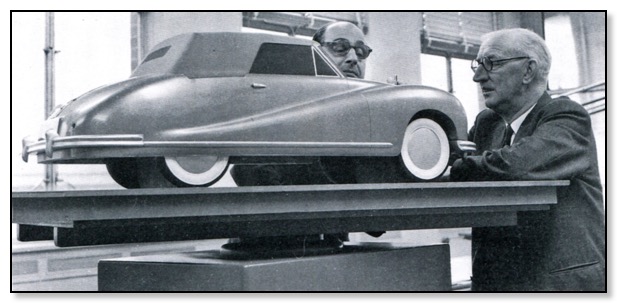

Austin Atlantic Mock-up

Lord himself was a highly accomplished draughtsman and a competent hobby artist. But, just as with Eric Neale and the A40 Sports and Jerry Coker for the Austin Healey 100, Burzi’s eye was more mature. Thus, when Lord personally penned the A90 Atlantic in 1947 it was the Italian who fine tuned the lines. The ‘Atlantic’s’ glamorous looks never appealed to a wide audience and it failed in the American market at which it was primarily pitched. Yet it has to be said, the ‘Atlantic’ was the most imaginative, and one of the best executed cars, to come out of Britain at this critical time.

There were times when Burzi was not quite as adept at refining his master’s ideas. One occasion, around the same period, is the mysterious case of the Austin Sheerline. Lord loved Bentleys and chose them as personal transport from 1939 until his death in 1967. Whether or not it was he who first coined the phrase ‘poor man’s Bentley’, there’s no doubt Leonard Lord wanted to produce such a model.

This time Burzi didn’t get it quite right. Abandoning the slab-sided, Packardesque models he was working on, and no doubt seeking to avoid any suggestion of plagiarism from Rolls-Royce at Crewe, he attempted a traditional razor-edge approach with incongruous Lucas P100 headlamps. While totally undeserving of the snide observation the car was the ‘best upholstered lorry in the world’, the timeless beauty of Ivan Evernden and Bill Allen’s design for the Bentley Mark Vl was simply not there.

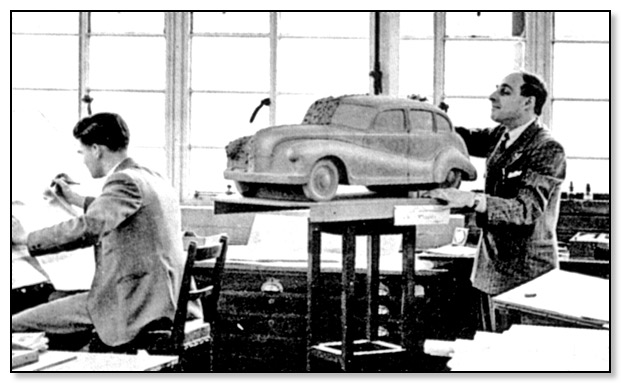

Clay Model For a Large Post-War Austin

However, Lord and Burzi could work in perfect harmony and clearly had a great rapport. A simple example is the creation, in 1947, of the ‘Flying A’ emblem. Lord handed artist, Gordon Crosby’s, sculptural winged ‘B’ radiator cap from his Bentley to the designer and asked for something similar. It was a poisoned chalice given Rolls-Royce’s propensity for litigation whenever their branding was threatened. However, in the space of a day, Burzi, demonstrating his creative talent, altered the slope of the ‘B’ and formed a stylised ‘A’ attaching a skeletal wing to the trailing edge. It was to become one of the industry’s most evocative symbols.

Much more significant was the pair’s anglicizing of both the revolutionary A30, the world’s first volume produced monocoque, and then the more prosaic A40 Somerset. In a highly imaginative move, Lord commissioned the iconic American consultant, Raymond Loewy, of Coca-Cola bottle and Shell Petroleum logo fame, to style his new ‘baby’ Austin. Holden Koto, a protégé of Edsel Ford, actually did the work but it was down to Burzi to neutralize the American’s brashness.

Flying 'A'

Similarly with the ‘Somerset’. It was Tucker Madwick, from the same agency, and, again, Holden Koto, who crafted the car; Burzi who put the Britishness back!

Many more archetypally ‘Austin of England’ designs were to flow from Burzi’s. studio. Whether Leonard Lord fully appreciated that the day of fierce overseas competition was nigh is unclear. He was certainly being goaded into doing so by journalists like Motor Sports’s Bill Boddy, who never missed an opportunity to attack the British industry. Burzi, as a stylist, may have been more aware. But by the mid-1950s and Austin’s golden jubilee, both men must have known the ‘game’ was moving away from America and closer to goals nearer home.

The popular account of Lord signing Pinin Farina as BMC’s design consultant is extremely dubious and discredits most of those involved. It has a gauche and socially inept Lord being embarrassed by His Royal Highness The Duke of Ediburgh during a visit to the Works and told the cars are ‘no good’, ‘undistinguished’ and not ‘up to the foreign competition’. The next day Lord sends for Farina, or, even more preposterous, Farina flies to Birmingham.

Little of this was HRH’s recollection when approached by this writer. And if one thinks about it sensibly, it wouldn’t be. Prince Philip’s ‘stock in trade’ was to put members of all sectors of society at their ease and he would hardly insult a vital department of a major company in front of its boss.

HRH does acknowledge that he suggested the cars might benefit from an outside designer and mentioned Farina as the first name that came into his head.

By the same token, it is unlikely Lord would snub a stylist he respected and had worked with successfully for 17 years. More probable, he and Burzi had been considering, over a period, a Continental accent for the cars. Lord knew Farina’s work well. The inspiration for the ‘Atlantic’ came from that source. While Farina had once been a partner of Vincenzo Lancia, with whom Burzi himself had cut his designer’s teeth. Burzi would also have known the broader Italian scene.

Inevitably, Dick Burzi would be over-shadowed when the newcomer arrived. Farina revolutionized the models. After the first, rather tame, although extraordinarily popular, A40, they became a different, more agressive, breed. With gnashing teeth and fins like scimitars. These were intended to be pan-European cars, not principally the carriages of English headmasters, dentists and plump dames.

Burzi took no part in the Mini. Nor did Farina, for that matter.

But he still had a role to play. Peripheral for the 1100 and 1800, then he and Farina worked together on the front and rear ends of the ungainly Austin Three Litre.

By now, Farina’s own star was waning, yet perhaps it is no exaggeration to say his style had matured over the years. For the last Austin Cambridge of 1961 the fins had gone, the grille was more subtle, the lines softer; a car more in the old Austin mode of Burzi.

The latter survived as late as the early stages of the Allegro. But this was the political age, of hatchet men and degradation. Even Issigonis, who had elevated himself to the status of public icon, was pitilessly humiliated. Burzi managed to retire - to Italy, around 1969, after 40 years at ‘the Austin’.

How can we assess him? There was plenty of disingenuousness around Longbridge in the 50s and 60s. A lot came Lord’s way; some Burzi’s. He was described as a ‘one week Italian designer’ which presumably means – nonsensically – he was only capable of one idea, and even more insultingly, as Farina and Issigonis’s ‘coffee boy’.

The truth is, Dick Burzi had an incredible talent, perhaps unique, for preserving the quintessential look of an Austin and lending a little bit of panache to raise it above the competition – the New Ascot, Lord-Look, the Devon and Dorset. And he could interpret Lord perfectly – the ‘flying ‘A’ A90 Atlantic and the Sheerline. He didn’t always get it right, who does? Mostly he did.

Leonard Lord may have been the styling inspiration. Ricardo Burzi was the facilitator.

This article is based on Martyn Nutland’s latest book, the first ever biography of Leonard Lord. Brick by Brick. The Biography of the Man Who Really Made the Mini – Leonard Lord is available from Amazon and other on-line booksellers. www.martynlnutland.com