For the Golden Jubilee a book was published, covering the

chapters of the Austin Motor Company over the first 50 years.

THIS, the story of our first fifty years, starts with the early years of a leader among men, an engineering genius possessed of vision, enterprise and tenacity.

Herbert Austin, the first child of Giles Steven and Clara Austin, was born at Little Missenden, Buckinghamshire on November 8th, 1866. His father and his father's father were farmers, his mother a naval captain's daughter. His home atmosphere was one of robust health, common sense and hard work. His schooling, first at Wentworth in Yorkshire, where the family went to live in 1871, and later at Rotherham, was thorough but uneventful except that he showed an early aptitude for sketching and presumably all alert and observant eye for detail.

At sixteen he went to Australia and in Melbourne joined with an Uncle who was Works Manager of a general engineering firm. Here he learned his craft the hard way but proved a willing and discerning pupil with an inventive turn of mind. During the next eight years he worked with six different engineering firms, acquiring always experience and self-assurance. He married at the age of twenty-one and at twenty-seven he was asked by Frederick Wolseley, by whom he was then employed, to return to England to supervise the manufacture of sheep shearing equipment.

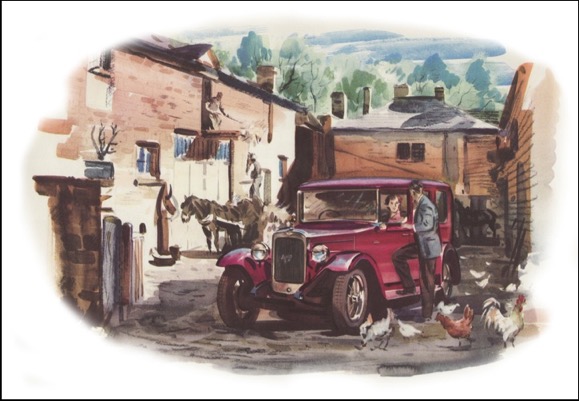

A new factory was set up for this in Birmingham and the firm prospered. Larger premises were taken over in 1895 and in the same year Herbert Austin built his first car, a tiller-steered three-wheeler. By this time his active, fertile brain was producing a steady stream of ideas and the advent of this new form of transport gave them great stimulus. Working mostly in his spare time, he produced a second car which was exhibited at the Crystal Palace in 1896.

The experiments continued, and in 1900 he built a four-wheeler with a horizontal single-cylinder engine, and entered it for the Automobile Club of Great Britain 1,000 mile trial. It won first prize. In 1901 the Wolseley Sheep Shearing Company, with Vickers backing, set up the Wolseley Too] and Motor Car Company. A works was taken over at Adderley Park, Birmingham, and Herbert Austin was installed as Manager. Under his direction, Wolseley cars of the next few years won international renown but in the early summer of 1905, after a dispute with the directors, he resigned and looked around for somewhere to start on his own. The man born to lead was moving towards his inheritance.

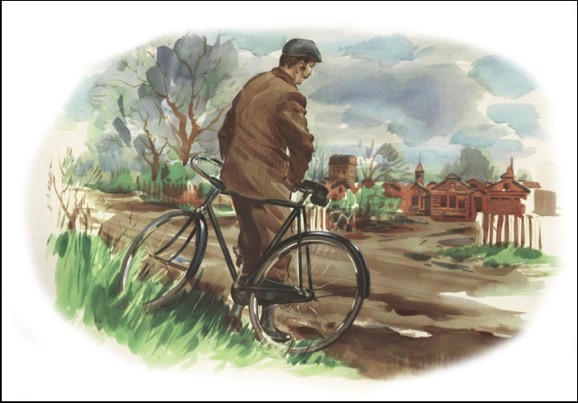

After numerous exploratory cycle rides around Birmingham he came to Longbridge, seven miles out of the City. There he found a small derelict works which proved to be just what he wanted. Last used by the firm of White and Pike Limited for the manufacture of metal boxes, it had been empty for four years. The Bristol Road ran past the entrance, the Midland and Great Western railways were alongside and all around lay the countryside. His friends said that labour and materials would be too difficult to obtain at such a spot but Herbert Austin saw further than they. Here he could expand, that was vital, other problems would solve themselves. All he now needed was financial backing.

He valued the land, works and fixtures at £10,000 and estimated that £7,900 would be required for additional plant plus an expected weekly outlay of some £600 to cover materials, wages and other expenses. It would be four months before the first chassis could be produced and thereafter the rate would be two a week. He estimated that the balance in hand after a full twelve months production would be about £8,150. As will be gathered, Herbert Austin was quite clear as to the design of his first car and plans were, in fact, already drawn up.

He got the money from Kayser, of the Kayser, Ellison Company advanced up to £20,000 and Harvey du Cross Junior, son of the Dunlop Rubber Company financier, and many others rallied round with additional help. So the Austin Motor Company was born.

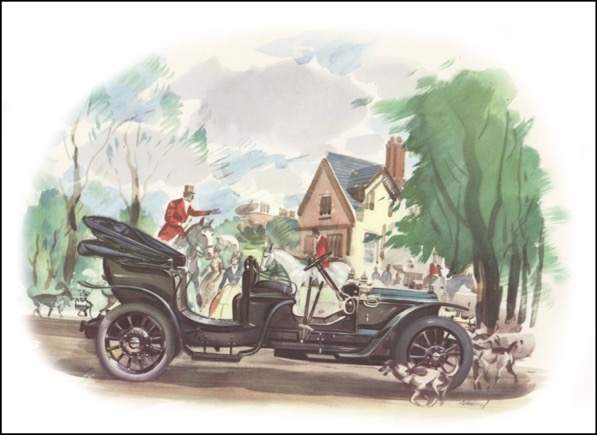

On November 17th, 1905, the Motor Show opened at Olympia. Herbert Austin and his two draughtsmen (A. J. Hancock and A. V. Davidge), complete with blueprints, high hopes and enthusiasm, sought orders and got them. On paper the first Austin was described as a 25-30hp high-class touring model with a 41/2 inch bore and a 5-inch stroke, magneto and coil ignition, a four-speed gearbox and a chain-driven rear axle. Only the highest class of materials would be used in its construction and the supervision during manufacture would be such as to secure the best results. it was expected that the first one would be delivered at the end of March 1906 and would cost £650.

After the Show it was hard work and long hours at Longbridge to get the first car on the road yet before March it was ready for trial and a few personal friends of Herbert Austin were invited to witness the event. It was a moment to be remembered. With the owner in control, the engine was primed, coaxed and bullied. It suddenly erupted and belched out clouds of blue smoke-too much oil had been applied in an anxious attempt to avoid a seizure. Then oil and petrol leaks appeared and the two coppersmiths responsible were promptly sacked. Herbert Austin, it is said, enveloped the scene with an output of fuming equal to that of the car.

But in the end all was well. The car left the shop, reached the road, made a very successful, if dusty, run and the coppersmiths were reinstated. On April 26th, 1906, a luncheon was given at Longbridge in honour of the new model and to celebrate the official opening of the factory. Eighty friends and trade notabilities were present and the toast was, " The Success of the Austin Motor Company ".

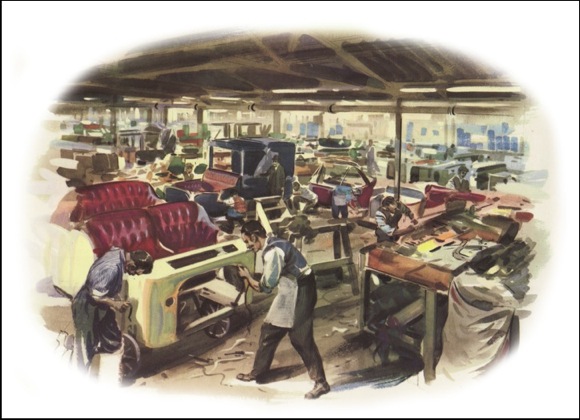

Skilled workmen soon found their way to Longbridge and in the first full year 270 of them turned out 120 cars in the original 21-acre factory. Expansion and extensions followed and other cars were added to the range. Austin coachwork, with its large selection of Phaetons, Limousines and Landaulets, also came to be admired and respected as much as the dependability of the chassis. Herbert Austin was thorough in everything - it is said of him at this time that he could do any job in his works, and that he knew the position of every machine. His men respected and admired him and the work went on at a cracking pace.

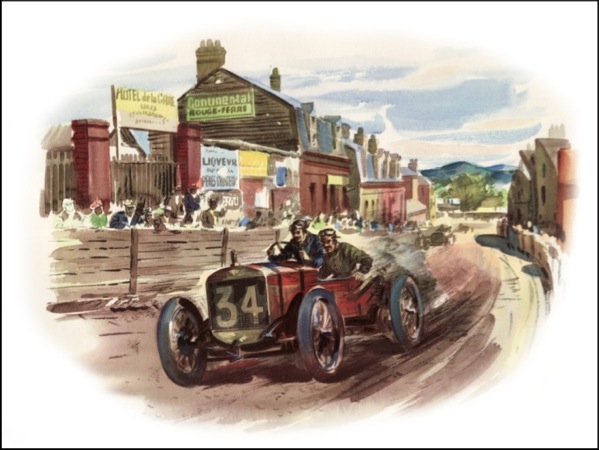

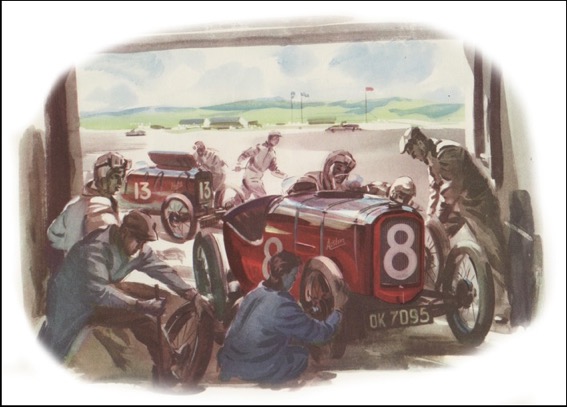

In 1908 three special 100 h.p. racers were built and entered for the French Automobile Grand Prix. Two of them driven by J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon (now Lord Brabazon) and Dario Resta came in fifteenth and sixteenth respectively, having given a very creditable performance. At Brooklands a private sportsman, 0. S. Thompson, driving a modified 25-30 h.p. Austin named " Pobble ", achieved constant successes. Others did well in reliability trials and in the hands of private motorists at home and overseas and the Austin reputation for dependability steadily grew.

By 1910 nearly 1,000 workers were employed and a night shift was found necessary. A single-cylinder 7 h.p. car and a 15 h.p. Town Carriage were added to a range that now included 10, 18-24, 40 and 50 hp. models and a 15-cwt. van. The sales organisation was extended both at home and overseas and such places as South Africa, Australia and New Zealand all had first-class Austin representation. More additions were made to the factory and an output of 1,000 cars a year was planned.

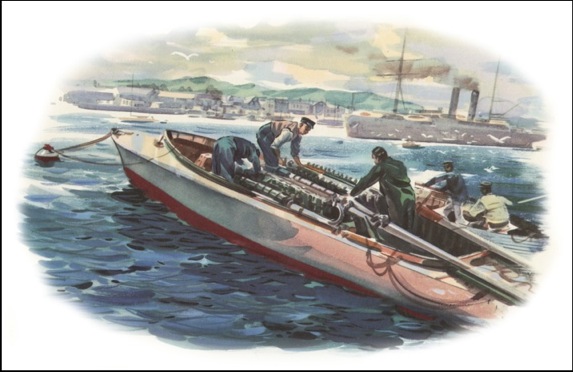

The interests of the Company now spread to industrial and marine engines, and in 1912 Saunders of Cowes built a speed launch which was powered with two Austin twelve-cylinder vee engines of 380 h.p. each. Named Maple Leaf IV, this launch won the British International Trophy two years in succession and was credited with a speed of 50-78 knots. Herbert Austin personally supervised the tuning of the engines.

The production of a 2/3-ton lorry in 1913 marked an excursion into yet another field. This vehicle had a 20 hp. engine and employed many novel features including a twin bevel drive and an underslung rear axle which permitted a very low loading platform. It was priced at £545 and a twenty-seater coach on a similar chassis was available at £765.

In February 1914 the Company changed from private to public ownership. The issue was immediately successful and the capital was increased to £250,000. Herbert Austin estimated that the expansion this would permit would increase sales to £550,000 annually. All seemed to be set fair and then the situation changed almost overnight. The Great War began.

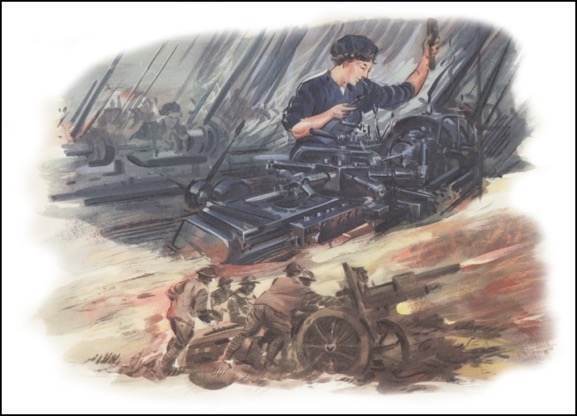

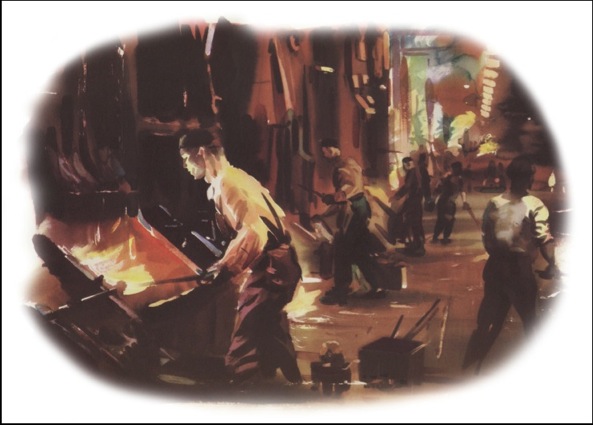

Within a few weeks the machines that had been building Austin cars began to turn out munitions. The drive, inventive genius and organising ability of Herbert Austin and all the resources of his factory were harnessed to serve the country in its hour of need. But as the appetite of the armed services for weapons and equipment of every kind continued to increase, the rapid expansion of the Longbridge factory became inevitable. It grew and grew until by 1917 it had trebled its size and in addition had its own flying ground on a flat-topped hill south of the main works. The number of employees, many of them women, rose to over 22,000 during the peak years.

Some idea of the Longbridge war effort can be gained by the fact that over 8,000,000 shells were made along with 650 guns, 2,000 aeroplanes, 2,500 aero engines, 2,000 trucks and a host of other items.

The factory that produced them teemed with new developments. Research and metallurgical laboratories were added, new heat-treatment plants installed and the manufacture of gauges and measuring equipment to extremely high standards of accuracy became almost routine procedure.

On the personnel side a labour department was established and a hostel for seventy-five boys was opened with the object of giving practical and technical engineering training to suitable youths. This development later blossomed into the Austin Apprenticeship Scheme which has since supplied many leading executives both for the Company and its distributors throughout the world, as well as for other leading engineering concerns.

Through all the stress and bustle of these wartime activities the founder of the Company remained the master, calmly directing with consummate efficiency the huge organisation that had suddenly sprung up around him. In 1917 he was created a Knight of the British Empire.

Nineteen-eighteen brought peace but, as is so well known, with it came problems that industry had not faced before. A tremendous production potential had been created for the supply of war material which suddenly was no longer required. In the lack of orders lay disaster since the strength of a factory is not so much in its plant and machinery, but is the rate at which that plant and machinery can be employed.

In the ensuing years many war-extended firms were to go under. For Austin the struggle was grim.

When times are bad the ability of a people or firm to weather the storm is always dependent upon the quality of their leadership. In this respect the Austin Company was indeed fortunate. Experienced as he now was in the organisation of a large industry, Sir Herbert yet remained an engineer and inventor. It was this very rare organisation of a large industry, Sir Herbert yet remained an engineer and inventor. It was this very rare combination of organising and practical ability which was to see the Company safely through the testing times that lay ahead.

Before the end of the war plans were announced for concentrating, when peace returned, on the production of a 20 hp. car only. This, it was thought, would be an economical proposition, and would meet general acceptance both at home and overseas. The car was entirely new and embodied many features resulting from war experience. It had a mono-bloc four-cylinder side valve engine of 33/4inch bore by 5inch stroke and a four-speed gearbox with a central change. The body was of much smoother and cleaner lines than pre-war and it was available as either a four-seater tourer, five-seater colonial car, or as a Landaulet. The price created a sensation, the tourer being only £495, compared with £700 for its 1914 counterpart, this despite the loss in value of the pound between the years. Unfortunately by 1920 a surcharge of £200 had been found necessary, one reason being, part from mounting costs, that bought new it was immediately being resold at a high premium second-hand in a car-starved home market.

This model proved in every way worthy of the Austin tradition and set a pattern in design which later Austins followed.

The engine used for the 20 hp. model was also adapted for a tractor, running on paraffin and having a drawbar pull of 3,000 lbs., which won many agricultural awards between 1919 and 1921. A 11/2 ton truck was also produced, using a similar power unit.

The Company's post-war programme included, for a short time, a range of aeroplanes! The Austin Greyhound two-seater fighter was one, and the Austin Ball single-seater another. Then there was a single-seater bi-plane, with folding wings, which sold at £500, and a fourth called the Austin Whippet. But these ventures were several years too early and had no proper place in a factory requiring continuous volume work.

In subsequent years, Sir Herbert Austin said that the reorganisation of the factory after the Great War was one of the most difficult jobs he had ever tackled, but it was managed eventually although not until 1921 could it be said that the scheme was complete. Meanwhile, despite the fact that many orders were coming in, the firm became involved in financial difficulties and an official receiver was appointed. Paid up capital at this time amounted to some £3,327,097.

Nevertheless the reputation of the Austin product was very high and the factory had a great potential for future production in the skill of its personnel, its plant and machinery and, especially since the war, its large-scale efficiency.

The Board of Directors was strengthened at this time. C. R. F. Engelbach was added as Works Director and E. L. Payton to give guidance on financial matters.

Thus Longbridge, in the midst of its troubles, was actually well prepared for the era of flow production. It only remained for the genius of the Chairman to design the right products and this he did in such a way as to command world-wide admiration.

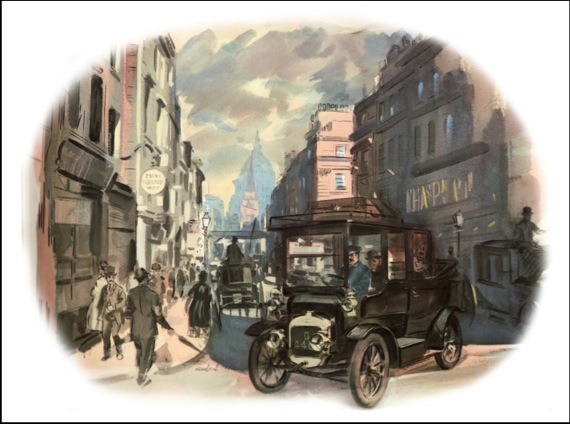

First in 1921 came the 12 h.p. car, which was literally a smaller version of the 20 hp model. This proved so successful that it stayed in production for nearly nineteen years and at one time was used by over 90 per cent. of the taxicab drivers in London. It had a four-cylinder engine of 2.13/16 in. bore by 4-in. stroke, a four-speed gearbox and a wheelbase of 9 ft. 4 in. The four-seater touring version at £ 550 was described as " a car of moderate dimensions which would fulfil ideals of service previously only obtainable in high-powered cars of 20 h.p. or over ". In fact, so efficient was its design that it changed but little during its long life.

And then in 1922 came the 7 hp. infant prodigy.

This was the real answer to the problem of the day, namely how to increase trade by increasing the number of motorists. It certainly helped to turn the tide at Longbridge.

The Receiver had already been sent packing with all debts fully paid and from that time on the Company never looked back.

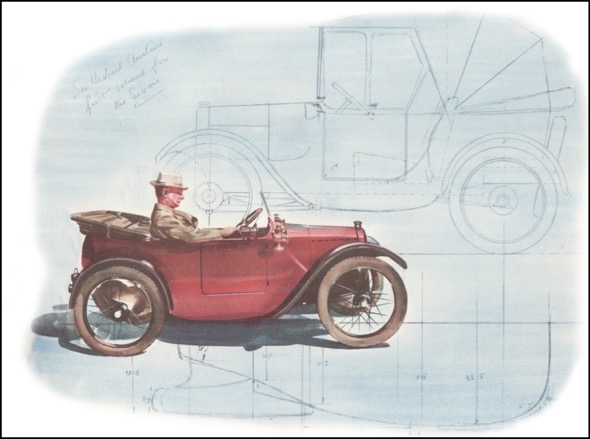

The Seven was at first received with much laughter and ridicule and few took it seriously. Not so Sir Herbert Austin. He had conceived it entirely on his own and, in fact, the drawings were prepared at his home at Lickey Grange only a mile from the factory. Despite all criticism he knew he had a winner.

The engine, with its 21/2in. bore and 3-in. stroke, developed 10 h.p. at 2,400 rpm. and was one of the smallest four-cylinder power units then made. But how sturdily it pulled. In many ways it was a large car in miniature, scaled down with that perfection of simplicity which is the hallmark of genius. It weighed only 9 cwt., had an overall length of 8 ft. 9 in. but still provided seating for four.

When the first Seven was completed, the mechanics of the Experimental Department watched Sir Herbert take his place in the driving seat to make the first run just as he had done seventeen years before when the first Austin car was ready for its road christening. But this time there was no fuming or commotion. The Seven started first time, moved briskly out of the shop and snorted happily up the road towards the Lickey Hills, the broad shoulders and bowler hat of its creator squarely silhouetted at the helm. A new era in motoring had begun.

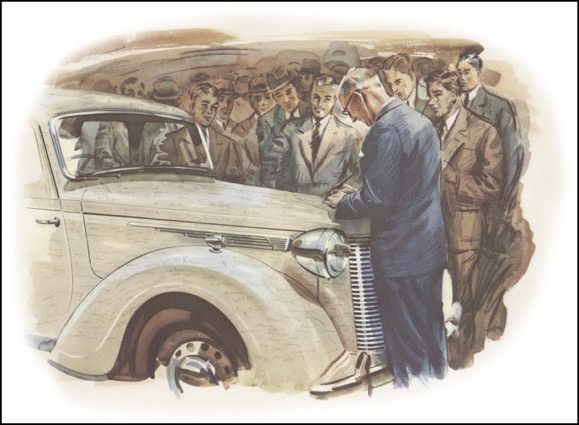

The Seven was exhibited at Olympia in 1922 at a list price of £225. People who previously had considered motoring beyond their pocket, examined it - the more adventurous bought one. The car exceeded their wildest expectations and the motoring journals published enthusiastic reports. A. C. R. Waite, who previously had won sporting events at Brooklands and at Shelsley with the 20 hp. car, began racing the Seven. It won at Brooklands and it won at Monza in Italy. In fact, it became a vogue and orders from all over the world began to roll in. The tempo at Longbridge quickened in response. The huge plant, that since the war had been sorely tried to find sufficient exercise, was now able to loosen up in every limb.

The sales and service organisations were stimulated to greater efforts. An effective distributor and dealer system was built up to give complete coverage throughout Britain, and overseas permanent representatives were appointed.

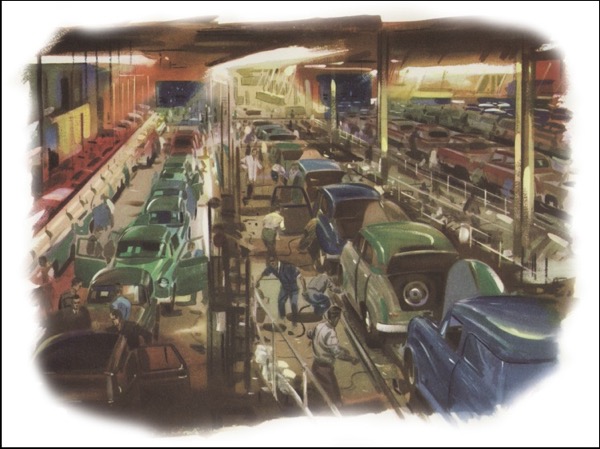

In 1925 and 1926 extensions were made to the factory so that it covered 62 acres of a 220-acre site and gave employment to 8,000 workers who annually produced 25,000 cars. It was freely claimed that Longbridge was the largest self-contained motor factory in the country, where could be seen more of the processes involved in the production of a car than anywhere else. Longbridge had, indeed, become a great engineering centre, with its own foundry, forge and machining shops, its own body pressing, assembling and painting plant, which now included the new spray-applied cellulose, and its own erection shops for both individual units such as engine, gearbox, rear axle and steering, as well as for the final assembly of the finished car.

Sales in 1925 amounted to £3,900,022 for the home market and £874,771 for export. These rewarding figures had been earned by a range of cars still comprising 20 h.p., 12 hp. and 7 hp. models, although the two larger were available in a number of body styles, including saloons which were now beginning to oust the standard tourer.

Nineteen-twenty-six witnessed the twenty-first anniversary of the Company, which was celebrated by a gala day to which all the workers and staff and their friends were invited.

In 1927 a new six-cylinder 20 h.p. car was marketed, which for a brief while ran in parallel production with the four-cylinder 20 h.p. model and then replaced it entirely. This car became the aristocrat of the Austin range and with saloon and limousine body-work that graduated through the names of " Carlton ", " Ranelagh " and " Mayfair " offered motoring at its superlative best at astonishingly low cost. In fact prices were now beginning to reflect the increasing efficiency of the factory. The 20 hp. dropped to £625 in 1924, and to £530 in 1929. Other models were similarly reduced.

The next few years covered a period of consolidation and steady progress. Sir Herbert Austin was not the man to change the design of his cars unnecessarily, but whenever he thought an improvement could be made, he made it. But it had to be an improvement-change for change's sake he never would accept ; it ran too strongly against his practical engineering outlook. He was thorough and he was alert to new ideas, as witness the fact that he took out over 180 patents in his own name during his life. But he was first and foremost an engineer whose reaction to any new method was " does it do the job better and more efficiently?" If it failed that test he had no further interest in it.

As six-cylinder engines were becoming more popular, Austin introduced late in 1927 a new 16 hp. car with a six-cylinder engine and the range then comprised twenty-four distinct models. In 1929 the number had increased to twenty-eight and prices had all fallen, the Seven tourer selling at the low figure of £130. This was indeed a justification of the policy of flow production especially when it is realised that the performance, styling, comfort and refinements of the cars were steadily improving.

By 1930, output had reached the record figure of 1,000 vehicles a week and the Company had every cause to be pleased with the advance it had made during the previous ten years. The early thirties provided a few economic difficulties but the organisation was now strong and virile enough to cope with them. The main effect of these difficulties, and the necessity to seek out business wherever it might be found, meant that the range of models tended to increase. Already there were 7, 12, 16 and 20 h.p. cars. Then in 1931 a 12-6 appeared, to be followed in 1932 by an entirely new Ten.

Meanwhile, the Seven had become the most popular small car in the world, and was being made under licence in the USA., Germany and France. It continued to astonish and thrill motorists with its sterling qualities and climbed Ben Nevis in October 1928 in 7 hours 23 minutes, and Table Mountain in 103 hours. Third and fourth in the Ulster International Road Race in 1929 it won the 500 Mile Race at Brooklands in 1930. With Malcolm Campbell at Daytona Beach in 1931 it achieved the commendable speed of 94-03 m.p.h. and later exceeded 100 m.p.h. at Brooklands with L. Cushman at the wheel, been the first 750cc car to achieve this speed in England. Wherever motor racing took place, there you would find the gallant Seven gladdening the hearts of enthusiasts with startling turns of speed and unbelievable dependability.

The elaboration of the Austin range continued, until by 1934 the situation was reached when the production men had the unenviable task of providing the enthusiastic public with a choice of forty-four separate models, based on nine alternative chassis. Taking into account the wide range of colours and equipment offered, a grand total of three hundred and thirty-three different cars were listed. Obviously this policy could not last for long, but it did in effect obtain until 1937 when the Cambridge, Ascot and Goodwood cars appeared.

In the 1936 Honours List, Sir Herbert Austin, who had for long been affectionately called the " Father of the British Motor Industry ", was created a Baron and took the title of Lord Austin of Longbridge.

To the non-discerning optimist there was no cloud in the Longbridge sky during those happy, prosperous years of the middle thirties. The factory buildings, which now covered 100 acres,, were humming with activity and goodwill. The order books were full. Austin cars were in constant demand everywhere and their reputation for dependability was world-wide. Yet there was a cloud somewhat bigger than a man's hand, beginning to dim the bright rays of this prosperity-the approach of another world war.

It must have been with a very heavy heart that Lord Austin, in his sixty-ninth year, accepted the Chairmanship of the Government-sponsored shadow factory scheme for aero-engine production. The last war had robbed him of his only son and its aftermath had very nearly wrecked the organisation which he had striven so hard to build.

But again he gave of his best in the interests of his country and during the next few years he devoted many hours to this new responsibility, particularly to the organising of the Longbridge part of the scheme. This involved the construction of an entirely new factory at Cofton Hackett, which fringed the southern edge of the Austin flying ground, where it was intended that both aero engines and aircraft would be produced.

But the war was still in the future and 1937 saw the introduction of the Big Seven and the Cambridge 10 h.p., Ascot 12 h.p. and Goodwood 14-6 hp. models. Also in the range at this time were the famous 18 and 20 hp. saloons which offered such roomy and luxurious motoring, while on the race track the latest version of the Seven, with its twin overhead camshaft engine producing 116 bhp. at 9,000 rpm., was sweeping all before it. Home market sales increased by 35-4 per cent. over 1936, export by 105-1 per cent. and net profit after tax amounted to £877,077. Over half a million pounds was spent on plant extension.

In March of the following year L. P. Lord joined the Company as Works Director. At the early age of forty-two he had made a brilliant name for himself as Managing Director of the Morris, Wolseley and MG. Companies and subsequently as Manager of Lord Nuffield's £2,000,000 trust fund for special areas. At Longbridge his career was to reach fulfilment.

The Cofton Hackett aero factory was then in operation and the first Austin-built aeroplane, a Fairey Battle, had flown from Longbridge. Meanwhile at the main factory, as a result of the new Works Director's enterprise, Austin re-entered the 2- and 5-ton commercial vehicle field. The new trucks were designed for economical running with maximum pulling power from an overhead valve six-cylinder engine and needless to say dependability was built into their every inch. They were announced in January 1939 and proved a success from the start.

In February a new Eight, of unit construction, was introduced to replace the Big Seven and a Ten followed in May. The last new model to be announced before the second world war was the Twelve in August.

On September 3rd, 1939, no one knew exactly what the future held, but one thing was clear. The country would need arms and munitions in great quantities and one of the key centres of such production would be Longbridge. It already possessed deep air raid tunnels to accommodate 15,000 people, and its machine shops had for some time been engaged in the manufacture of a number of items which were to be labelled WD.

So, as the alarm sounded Longbridge sprang to action stations and in a sense disappeared. In three hectic days the whole works was blacked out, over 120 acres of roofing was camouflaged, and within the comparative safety of this disguise against air attack the factory became a veritable hive of reorganisation.

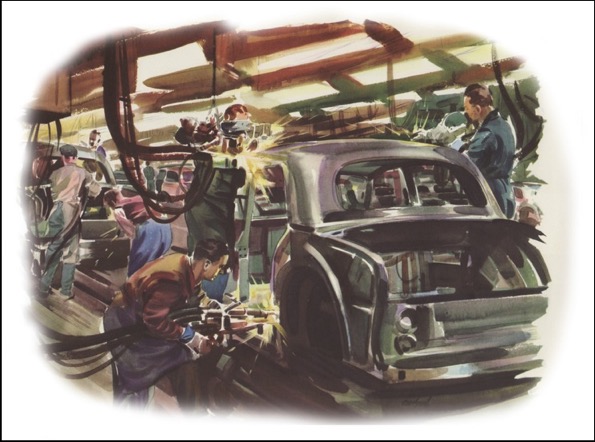

If ever evidence was required that what matters most in a factory is the skill, ability and spirit of its people, then Longbridge provided that evidence in the early years of the war. The same brains and hands that a short time before had turned out highly finished cars took in their stride the production of a whole miscellany of intricate parts for the nation's war machine.

As Government contracts were received, men, women and machines saw that they were fulfilled in the quickest possible time. As soon as one contract was completed another took its place. The variety of items produced was legion, as also were the quantities. Over one and a quarter million rounds of 2-, 6- and 17-pounder armour-piercing ammunition and twice as many ammunition boxes; over half a million jerricans, nearly as many steel service helmets and hundreds of thousands of assemblies of one sort or another for mines and depth charges. A mere hundred thousand bogey suspension and driving gear units for Churchill tanks was considered almost a side line.

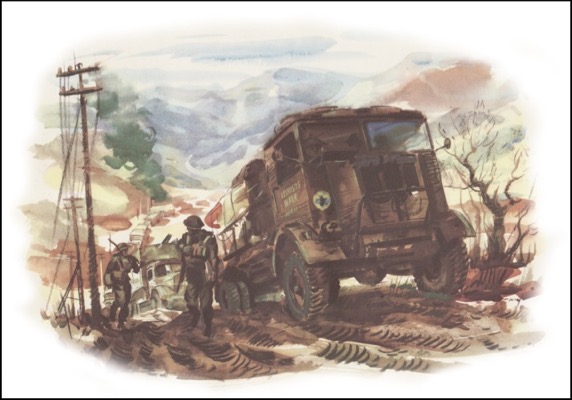

And all this against a steady output of wheeled vehicles of various types ranging from Eight and Ten Utilities to four- and six-wheeler trucks with four-wheel drive, used as general service vehicles, gun portees and R.A.F. tenders. The Austin K2 Ambulance was another great production. Thirteen thousand were built and one, captured at Dunkirk, served the Nazis on the Russian front before being regained by the 21st Army Group at Commeux. Field-Marshal Montgomery ordered it to be returned to Longbridge where it was found to be stiu in good running order. Thus Austin met a very large part of the wartime transport needs of the armed services and over thirty-six thousand of the heavy types of vehicles were built.

The shadow factory at Cofton Hackett, which started production with Fairey Battle light bombers and Mercury and Pegasus aero engines, ended by turning out Lancaster four-engine heavy bombers. the latter were too big to be flown from Longbridge flying ground and were assembled a few miles away at a separate airfield, as were the Stirling bombers which preceded them. Nearly three thousand of these machines, along with Hurricane fighters, Beaufighter and Miles Master fuselages, was a very creditable effort for a factory which virtually started from scratch.

At the height of the war over 32,000 personnel manned the Austin production front. Their united contribution was immense yet apart from one daylight raid by a lone bomber, the factory was left unmolested from direct attack by air throughout the war-another advantage, perhaps, of its countryside location. Had Longbridge been at the centre of a huge agglomeration of factories, warehouses and offices, it would undoubtedly have suffered more.

Thus again time confounded those who doubted and advised Herbert Austin against building his factory so far out of Birmingham. He made his mistakes, as do all men,, but his big decisions were nearly always right. To a lesser degree his genuine and sincere interest in hospital equipment and welfare, towards which he contributed many thousands of pounds, and his magnificent gift of a quarter of a million pounds to the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge, where Lord Rutherford's pioneer investigations into atomic and nuclear energy were to prove so startlingly successful, will bear witness for many, many years to come, of his personality, generosity and widespread interest in the country of his birth and its people.

Lord Austin died on May 23rd, 1941, after a short illness. He was succeeded by E. L. Payton who retired four years later, on November 28th, 1945, whereupon L. P. Lord became Chairman and Managing Director. Thus commenced another epoch at Longbridge.

As with Sir Herbert Austin after the Great War, the impact of the new Chairman's drive and vision on the fortunes of the Company in the post-World-War years was to prove decisive. Nineteen- forty-five saw Britain victorious, triumphant and financially almost broke. Dreams and schemes of a higher than ever standard of living were many. Only the far-sighted realised that it could be earned only by hard work and greater output. L P. Lord was such a man and he at once made plans for a rapid expansion of Austin production to expand its overseas marketing.

The 1919 error of concentrating on one model only was not repeated, nor the vast and complex range of cars of the between war years. Austin was to manufacture Fight, Ten, Twelve and Sixteen cars, the latter being powered with an entirely new four-cylinder overhead valve engine. Most of the jigs and tools for these models had been carefully preserved at the commencement of the war. Now they were taken out of storage and put to production.

The first model to appear was the Ten, which was given a helping hand by the Ministry of Supply which ordered large numbers for early delivery in 1945. Naturally enough the Ten was almost identical with its pre-war counterpart but there were detail refinements to the chassis which gave improved performance and dependability. These refinements were in many instances the direct result of war-time experience. The patent timing-chain tensioner, non-loss radiator and patent crankshaft lubrication were but three examples. Nevertheless material shortages prevented an immediate return to previous standards in some respects. For quite a time the Ten, and other models, were supplied with a spare wheel, less tyre, and where colours were concerned the customer could choose any one he wished providing it was black.

The Eight quickly followed the Ten and then came the Twelve and the Sixteen. These two cars were identical in appearance, but whereas the former had the pre-war four-cylinder side valve engine of 1,535 c.c. capacity, the latter had a four-cylinder overhead valve unit of 2,199 c.c. capacity. The performance of the Sixteen was extremely good and in a sense it was to set the pattern for the post-war Austins in the same way as the 20 hp. had done in 1919. L. P. Lord was determined that in future the traditional Austin dependability would be enhanced by a sparkling road performance-the Sixteen fulfilled this aim.

Meanwhile within the factories at Longbridge another revolution was being planned; one which was to send production to heights unthought of in 1939 when the maximum weekly output rarely exceeded 1,600. As soon as machines were released from Government contracts they were modernised and repositioned for flow production. The old belt driven machines lined up rigidly beneath long lines of shafting and pulleys were discarded for the neater, simpler and more efficient and flexible individually powered units.

The impact of this change was most noticeable in the engine factory where the more modern machine layout was matched by a new assembling section. Here an entirely new conception of production was put into practice. All the parts required for engine assembly were marshalled in a stores and placed in suitable container sets on the assembly track which then carried them, via a cleansing plant, into the assembly bay. Operatives thus built up the engines with all parts conveniently to hand. As soon as the engines were built they were run-in on a turntable which motored them at a steady speed while highly filtered oil at great pressure flushed out the bearings. These turntables prepared the engines in a much more efficient way than the old individual water and electrical brake systems and the saving in space, time and money was tremendous.

It was the same everywhere at Longbridge. The factory was being subjected to the biggest reorganisation it had ever known. Any person who thought they knew the detail layout of the various buildings could be out of date in a week!

And suppliers, who had coped fairly comfortably with the demands of wartime, found themselves staying awake at nights wondering how to keep up with Longbridge. In June the Millionth Austin, a Sixteen, was produced. This car, painted in a matt cream, was signed by the Chairman and the workpeople at a special celebration; the one before the millionth, and the one after, were awarded by ballot to fortunate employees.

Statistically this millionth Austin entailed a week's work by nine men. In 1926 it took sixteen men a week to build one car and in 1910 it took one hundred and four. Total cumulative output by 1920 had reached 15,000 and by 1933 the figure was 333,000. This reveals how great was the change in production following the Great War, and with the second million Austins equally startling results were to be achieved.

The winter of 1946-7 was one of the severest on record, which gave added lustre to an epic " Seven Capitals in Seven Days " journey made by three Austin Sixteens from Norway to Switzerland. The cars and their drivers performed wonders and upon arrival at Geneva on schedule they were congratulated by the Austin Chairman in person. This arrival coincided with the Motor Show which was then in progress and where Austin aroused world-wide interest by exhibiting, for the first time, two entirely new cars, the Sheerline and Princess.

These models offered motoring at its very best yet at a remarkably low price. The Sheerline cost £l,000 while the Princess, with its coachbuilt body by Vanden Plas (a subsidiary of the Austin Company), was priced at only £I,500.

Both cars had a six-cylinder overhead valve engine, independent front suspension, steering column gear change and a hypoid rear axle. Their five- to six-seater coachwork, which was luxuriously equipped with built-in heating and radio, was modern and graceful yet distinctively British. On the road they were quiet, smooth but immensely powerful.

The designations of these new cars as A110 and A120 was the Austin answer to the change in U.K. car tax from a sum based on the RAC. rating to a flat rate. From this time onwards new models were designated by their approximate engine brake horse-power. Naturally enough everyone was glad to see the end of the old anomalous tax as, in future, engines could be properly developed to suit world operating conditions instead of Government legislation.

Shortly after the Geneva Show, L. P. Lord began what was to prove one of his boldest ventures. Britain badly needed dollars but to try and earn them in any substantial quantity by exporting cars to the United States was considered unrealistic. L. P. Lord had different ideas. He sailed for the USA. in May and after a close study of conditions returned to Longbridge and prepared for a large-scale attack on this most difficult of all markets for foreign manufacturers, with a car then in a forward stage of development.

The first production models of this new Austin, which came to be known as the A40 Devon, were available in August, and the Chairman, accompanied by G. W. Harriman, his Works Director, returned to the USA. taking two with him. Conventions were arranged, the cars were shown and the Americans liked them. Dealers were signed up and plans laid for shipping as soon as possible. A fully effective spares coverage by which Austin parts would be flown anywhere in the country within twenty-four hours was also planned. Thus began the great invasion of this hitherto unassailable market by the British Motor Industry.

Canada, too, became an integrated part of this drive for dollars and old Austin distributorships and dealerships were greatly strengthened and new ones appointed. As the new A40s began to arrive and pass into the hands of the public the large car minded American motorists came to marvel at their performance, the outstanding economy and their smooth, comfortable riding. Sales increased and dollars streamed back to Britain.

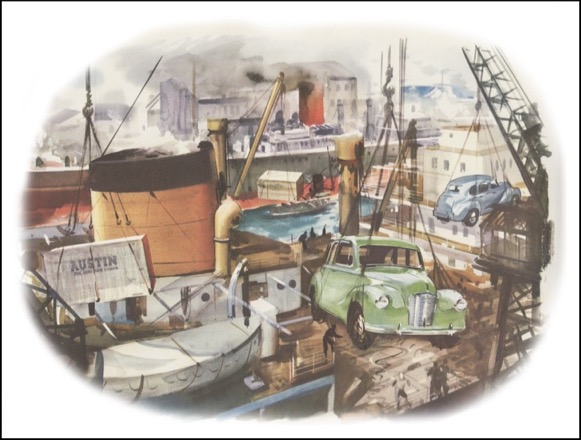

At Longbridge production was steadily rising. While the Eight, Ten and Twelve cars, which had served so well during the immediate post-war years, were now replaced by the A40, the Sixteen continued in production along with the new luxury Sheerline and Princess models. The output of 2- and 5-ton trucks and of the 10-cwt. and 25-cwt. light commercials proceeded apace. In the financial year ended July 31st, 1948, the total production reached 85,400 vehicles of which 54,054 went overseas. Total export earnings amounted to over £30,000,000, but even greater achievements lay ahead.

By this time the Austin organisation with Companies formed both in Australia, which has consistently proved to be Austin's best export market, and in South Africa, was indeed world-wide. Wherever a market existed for vehicles, Austin representation was established. Personnel from the factory travelled many thousands of miles studying conditions, organising service, negotiating agreements and keeping abreast with the complicated and constantly changing regulations relating to import licences, quotas, tariffs and currency.

As one market closed so another was almost literally prised open. Sample models were sent in, demonstrated, accepted and ordered. The production lines at Longbridge continued to increase the supply and the Austin Motor Export Corporation directed the flow to ports all round Britain in a continuous effort to find the ships to get the vehicles away.

At the 1948 Motor Show at Earls Court, the first held for ten years, Austin announced two new models, the A70 Hampshire and the A90 Atlantic Convertible. The latter model, with its hydraulically operated hood, was the centre of admiring crowds. It had twin carburettors, overhead valve engine, and streamlined bodywork quite unlike any previous Austin.

That the A90 had a superb performance, with traditional dependability, was later proved at Indianapolis ]in 1949. On this famous American race track a standard car hurtled round continuously for seven days and nights covering 11,850 miles at an average speed of 70-54 m.p.h. It established 63 new stock car- records and collected 27 US. national records. Later in the same year an A70 Hampshire set up a new record for the England to Cape Town run, covering the journey in 24 days, 2 hours and 50 minutes.

By July 3rd, 1949, annual production had reached 126,685, in 1950 it rose to 157,628 and in 1951 the magnificent total of 162,079 was achieved, 114,609 of these going to export markets. And the biggest contributor to this fabulous achievement was the A40. By November 1950 over a quarter of a million of this model had been produced which earned no less than $70,000,000 for Britain.

Thus within five full years of the end of the war, production at Longbridge had increased by over fifty per cent. on pre-war Output and this Without any significant change in factory acreage or in the number of employees.

But while all these records were being achieved the Longbridge engineers, were pursuing even further plans for Increasing production efficiency. A new car assembly building was taking shape which would be the most modern of its kind anywhere in the world. The aim was to make maximum use of electronic controls for the automatic selection, sequencing and feeding of parts to the assembly tracks. The problems which had to be overcome to achieve this were immense but under the guidance of G. W. Harriman, now Deputy Chairman, whose unique production engineering ability had proved so invaluable to the Company in its post-war reconstruction, success was achieved. The new building, erected on the old flying ground, and fed by a vast system of underground conveyors, was opened by the Minister of Supply on July 19th, 1951. With its four assembly tracks it had an output potential of one vehicle every forty-five seconds and provided first-class working conditions for the employees.

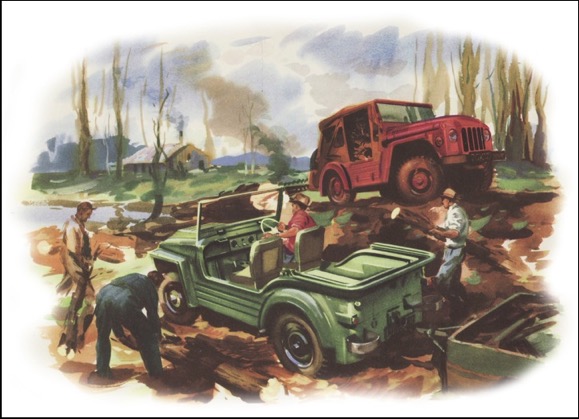

Another very significant move at this time was the acquisition and re-occupation by the Company of the Government owned Cofton Hackett Aero Factory. Austin trucks had proved most successful and more space was needed for their production and for the fulfilment of Government contracts for 5-cwt. and 1-ton four-wheel-drive general purpose vehicles. The former, which had been largely developed by the Nuffield Organization, was to become popularly known as the " Champ ", and was an unsuspected herald of later developments, namely combined operations under the soon to be formed British Motor Corporation Ltd.

Thus it was that during 1951 and 1952 a considerable amount of factory alteration and development was in progress. More and more earnings were being ploughed back into the Company, over tbree-quarters of a million pounds alone being invested in new plant for the bonderising, priming and painting of bodies. In this new plant, shining steel bodies received complete protection against rust and in the subsequent paint section new type conveyors, with counterbalanced slings, carried them through section after section where detailed attention was given to cleaning down, priming, painting and oven baking, to produce a smooth, lustrous finish of lasting quality.

Model-wise, the 1950 Motor Show saw the announcement of the A70 Hereford, and twelve months later came the A30 Seven. These were followed early in 1952 by the A40 Somerset, as successor to the popular Devon, and then at the 1952 Motor Show occurred one of those events which so clearly show the enterprise of the Austin Chairman. Seeing on the Healey Motor Company Stand a new sports car with the Austin A90 engine and other basic Austin units, he made an agreement there and then with Donald Healey to produce the cars at Longbridge under the title of the Austin Healey Hundred. And so another famous model joined the ranks.

By 1952 the Company seemed at the very peak of its fame. Its factory site covered 250 acres and over 19,000 were employed in producing a range of models that had gained world acceptance. The Company also had earned since the end of the war well over £150,000,000 in foreign currency. Yet even further development lay ahead. The Austin-Nuffield merger, first mooted even in the early history of the two companies, and revived in 1949, was announced as a firm fact in November, 1951, and became final in July, 1952, when The British Motor Corporation Ltd. came into being.

Here was the opportunity for two of Britain's leading manufacturers to pool experience and productive capacity to give the public even finer motoring at competitive prices and supported by a comprehensive parts service.

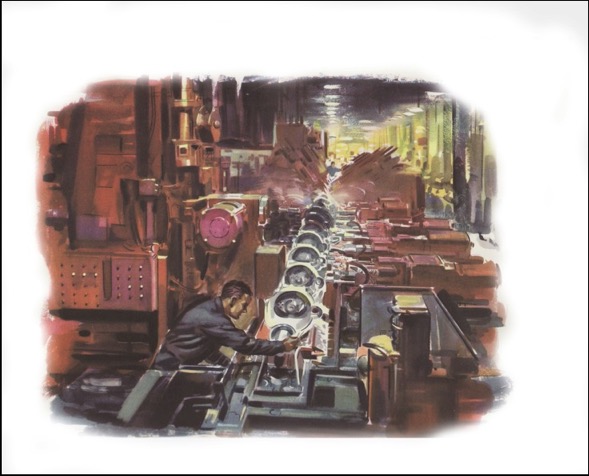

At Longbridge, as at Cowley, Coventry and Birmingham, factory reorganisation was commenced anew with the same efficiency and speed that had characterised the solving of the immediate post-'war problems. A new engine factory was planned and a new production technique, which was already far advanced, was adopted. Transfer machines, which each replaced up to twenty-five orthodox machines, had already been built by Austin engineers. Requiring only a few operatives each, these huge installation machined such parts as engine blocks and gearbox casings, with a rhythmical precision achieved by electrical synchronisation. The operatives had only to load the rough castings or forgings at one end and unload the finished components at the other-everything else was done automatically. The advantages of these machines in increasing production efficiency and conserving factory space were so outstanding that more and more were constructed and are still being constructed, for use throughout the BMC. group of factories.

But while the Longbridge potential was being shaped to the new pattern, current production was fully maintained. On November 26th, 1953, the second millionth car was despatched and plans were well advanced for building, in co-operation with Fisher and Ludlow Limited of Birmingham (later a BMC. plant), a light car for the Nash Company of the USA. This new model, which Nash were anxious should make use of as many A40 parts as possible, including the engine, was ultimately announced on March 19th, 1954, as the " Metropolitan". Its reception in the North American continent, where it was to be exclusively marketed by the Nash Company, was at once most encouraging. Since then many thousands of these cars have crossed the Atlantic to earn dollars for Britain.

Another product which had also established itself as a dollar earner was the Austin Healey Hundred. The Americans had taken a great fancy to this lithesome car with its 100 mph performance, and record speeds achieved at the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1953 and 1954 did much to confirm their appreciation. On one occasion during the later runs a supercharged version of the car achieved 192-6 m.p.h. over the measured mile.

On September 28th, 1954, the successor to the A40 Somerset was announced. It was a completely new car, of unit construction, with sweeping lines, and a choice of 1200 c.c. or 1500 c.c. engines. Named the " Cambridge ", after a famous Austin forerunner, the new car was at once in great demand throughout the world, and it was shortly followed by the announcement of a new six-cylinder model to replace the A70 Hereford. With the A90 Six Westminster, as the new-comer was called, the A135 Princess, Austin Healey Hundred, A40,/A50 Cambridge and A30 Seven, the range of cars became brilliantly and competitively complete. On the commercial side, new light vehicles with capacities from 5 to 30 cwts. were released at the 1954 Commercial Show and on March 9th, 1955, came the brand new range of 2/3 and 5-ton trucks with normal or forward control and BMC. petrol or diesel engines.

This, then, in brief outline is the story of our first fifty years. It is a story of which to be proud but more essentially one to give confidence in future endeavour. The present Chairman, Sir Leonard Lord, who was created a Knight of the British Empire in the 1954 New Year's Honours list, is carrying the torch handed on by Lord Austin. We await the future with eagerness and optimism.

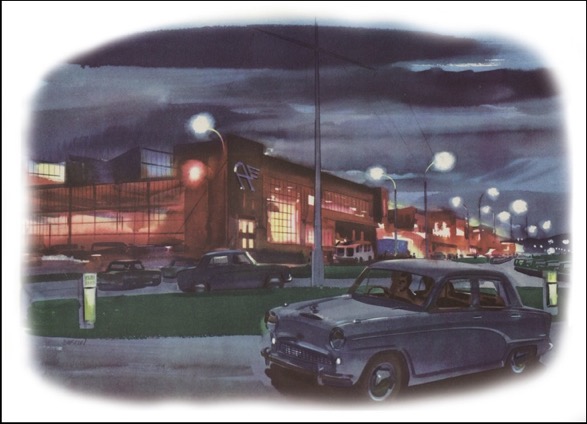

CAB 1 at Night

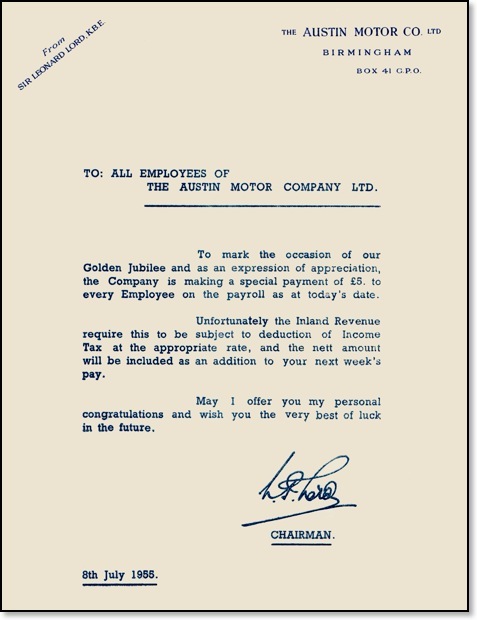

Each employee received an envelope on Pay Day with a letter from Sir Leonard Lord KBE saying that they would receive a bonus of £5 at next Pay Day.

So from the Blue text we know that Mr A Stanton worked in

West Works (W) and his Check No was 18440

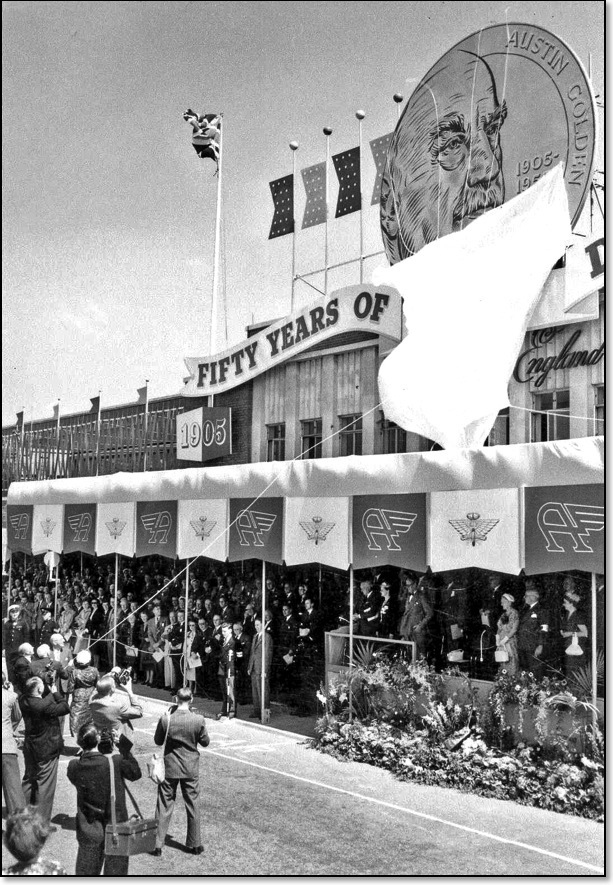

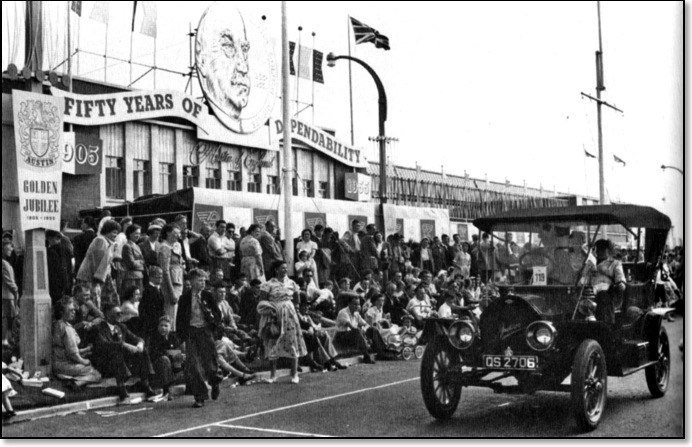

The Austin Motor Company to-day employ more than 20,000 people, who produced more than 120 vehicles every working hour, said Sir Leonard Lord, chairman and managing director, when he started the Jubilee celebrations of the firm at Longbridge, Birmingham, yesterday. He said that 50 years ago, when the Longbridge factory was started by Herbert Austin, it employed fewer than 250 people and in the first year produced 120 vehicles. More than 2,320,000 cars and commercial vehicles had been produced in the 50 years.

Mr. Harry Austin, aged 78, brother of the founder, unveiled a plaque 30ft. high in memory of his brother. Austin distributors from the Commonwealth countries and from the Continent, and most of the 20,000 employees with their families attended the celebrations.

The final event, a cavalcade of Austin cars from 1908 to the present day, contained the gas turbine-engined Austin Sheerline, which was announced last August but has not previously been shown to the public. A spokesman for the company said they were not yet ready to market-a gas turbine car.

For an article on Longbridge Gas Turbines, click on this LINK

A bouquet was presented to the Lady Mayoress by Miss Ann Stanley on the left.

The unveiling of the Plaque

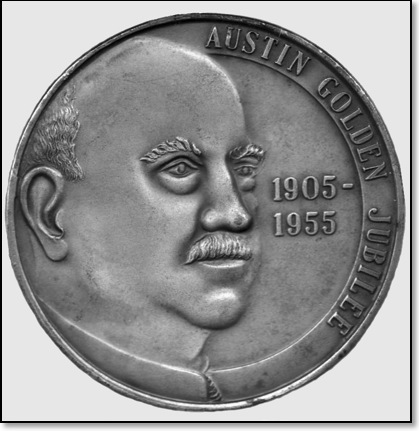

The coin came in a blue box, and was supplied by

D A Butler & Co 48-50 Vittoria Street Birmingham

Only a few of these coins were actually made, the exact number is unknown, (unless you know different). They were given out to people who had been in the cavalcade. It is believed that a few were actually made in gold.

One of the various cars in the procession passing the CAB assemble building.

____________________

Our First Fifty Years – And The Years Ahead

By Sir Leonard Lord

FIFTY years is a very short chapter in the story of human progress, but in the history of the motor-car and the motor industry it is almost all that matters.

When Lord Austin our founder, started at Longbridge in 1905 he designed and built cars which were basically the same as the car of today or yesterday-with vertical four-cylinder water-cooled engines, mounted forward in a chassis, transmitting their power to live axles, and with semi-elliptic springs and wheel steering, and a distinctive motor-car body so that the vehicle which resulted could be truly called an automobile.

The day of the horseless carriage, with chain drive from a horizontal engine, tiller steering and dog-cart body, was over. No vehicle of those tentative designs, of the exploratory days of the motor-car and motoring. was ever built at Longbridge.

Marching along

Purchasing and equipping his small 21-acre factory at Longbridge for the, manufacture of Austin cars, with £10,000 for the factory buildings and £7,900 for plant and working capital Herbert Austin was marching along with his contemporaries into the era of the true automobile, and his name was quickly to become famous.

In some respects he was ahead of his contemporaries for he was choosing to develop on an unrestricted' site in the belief that where there was work workpeople would come to it and with the faith that there would be plenty of work in a developing automobile industry.

I consider the organisation he founded was a good example and typical of the development of the industry as a whole at that time.

The first recorded figures of production of motor vehicles by the British motor industry are for 1908, when the year's output barely exceeded 10,000 units. In that year, three years after the start at Longbridge. Austin produced just over 400 vehicles or four per cent. of British production, and up to the First World War. Austin vehicles numbered 2,952 units, out of 111,000 turned out by the industry.

Formative years

These were the formative years, if I may call them such, when development of design, and the establishment of a sound reputation and a good name throughout the industry and the world, were more important than rapid progress in output. Indeed apart from a growing fund of goodwill, there were few signs to indicate the enormous expansion ahead of Longbridge. Certainly, less than three per cent. of the industry's output, was nothing to boast about before World War One.

It is probable that the hard lesson of that war of attrition, with the pell-mell production of the munitions essential to survival turned Herbert Austin's thoughts to quantity production made him study its principles and appreciate its possibilities. We must remember too, that in those years, Henry Ford was demonstrating its possibilities with the model T.

Thus, whether consciously or unconsciously, he evolved, in the very advanced design of his first post-war car the Austin Twenty a model eminently more suitable for quantity production and quantity selling than any of its predecessors. From that day, and with the advent of the Twelve and the Seven, the phenomenally successful baby, Austin output soared. Longbridge expanded, and the Austin Motor Company began to reveal its true stature.

Despite the problems of changing from war to peace time production, in the first full post-war year, namely 1919-1920. nearly twice as many cars were produced at Longbridge as in the whole history of the company, pre-war, and by 1923 Austin production was beginning to rank as a considerable factor in the British industry, with over 10 per cent. of that industry's output.

New models, new methods of production and a world awakened anew to the possibilities of motor transport, were the ingredients of a still more rapid rise in output and turnover in the next few years. By 1928 Austin's output had increased tenfold, and was nearly 20 per cent. of the total for the industry.

The old formula of experienced and enterprising designers, backed by a team of working craftsmen, was no longer valid. The production engineer, with his machine tool experts, and planners had appeared on the scene, leaving to the craftsmen, the vital task of tool making on the one hand, or on the other, the development of new designs and building of prototype models. There is no other explanation, for a ten-fold increase in production in ten years.

With 20 per cent. of the industry's business in its hands the future scale of Longbridge began to be revealed. By 1933 the magic figure of 1,000 units produced consistently each week, had been achieved.

Employment

All this added up to something more than output figures. The Austin combination of good progressive design and equally progressive production planning and development had by 1926 created an industrial unit employing over 8,000 people directly and at least as many more indirectly in the Birmingham area.

Longbridge and its surroundings was becoming a new and thriving community. By 1938 over 16,000 people were directly employed, and this figure was to double during the second world war with the addition of the adjacent Air Ministry factory, managed and operated by Austin.

The Austin factory, or group of factories now form the centre of a thriving group of communities and the green fields formerly surrounding the once tiny one-and-a-half acre works, now for a mile or so are largely occupied by the pleasantly situated homes of Austin workers, and the tradesmen who serve them. This is the social measure of what has been achieved on the foundations that Lord Austin so well and truly laid.

Increasing work

For Birmingham as a whole it has meant ever increasing work for many of her workshops which serve the motor industry. In 1954 Austin spent over £25,000,000 with local suppliers and over £500,000 on services from Birmingham including electricity and gas, while paying more than £13,000,000 to its own employees. Big as Birmingham is, that is a very great contribution to her industrial prosperity.

But I must in justice also mention that the products of Longbridge have also contributed greatly since the war to the solution of Britain's foreign exchange problem. Since World War II, Austin exports have earned for Britain well over £300,000,000 with over 730,000 units shipped overseas, and included in this figure are 155,000,000 dollars earned in opening up the dollar markets of the new world.

We in the motor industry have just seen the completion of our plans for the first stage of post-war expansion. At Longbridge this was to produce 4,000 vehicles a week. We are in fact, well on the way, with our next stage of development, enabling us to produce over 6,000 units a week, which we expect to achieve early next year, being now at the 5,300 mark.

For this expansion, considerable expenditure, and much re-planning, has been necessary not only of buildings and plant, but also of products. We are fortunate, within the framework of the British Motor Corporation, to be able to achieve these results most economically by co-ordinating our efforts with those of our great partner, the Nuffield Organisation, which itself will be producing some 6,000 units weekly in nine months or a year's time.

This, then is the future a bright one but charged with ever increasing responsibility for everyone concerned throughout the organisation. For to maintain or improve quality, combining it with advanced but sound design, while increasing output is not enough. Austin products must continue to be keenly competitive in a price sense, and must represent the best value for money in a world that is becoming more and more price conscious.

In its simplest terms, this is the test we face. It will require all our resources and all the ability and loyalty of our people, but we are inspired by the example of our founder and with that we cannot go wrong.