W A Howitt - Herbert Austin Personal Secretary

Mr William Arthur Howitt at his Office Desk, late 1910s

I first became Private Secretary to Mr. Herbert Austin during his Managership of The Wolseley Tool & Motor Car Company at Adderley Park, Birmingham, and when in 1905 he severed his connection with that Company, to commence motor manufacture on his own account, he invited me to accompany him. I am now in my fiftieth year at Longbridge, being, in length of service, the oldest member of the staff. It may be asked what was the reason for locating the Austin Motor Company at Longbridge. It was Herbert Austin's own far-sighted idea to obtain a property on the outskirts of Birmingham, road and rail facilities in the vicinity and with room for expansion, as he knew the organisation would expand. His friends tried to dissuade him from this, stating that he would never get the mechanics to leave the city for work in a country district, quite apart from the transport difficulties that had to be overcome.

Herbert Austin, however, stuck to his opinion, and eventually purchased the old printing works at Longbridge. They were the property of Mr. Olivieri, the wine merchant of New Street, Birmingham, and as I personally took the letter from Mr. Austin to Mr. Olivieri to complete the deal, I often think of that historic occasion when passing the wine shop in New Street, which still functions in that capacity. The wisdom of his choice of site has been abundantly proved, as it was found that the mechanics were willing to come out into the country, and although at first they had to walk from Northfield railway station to Longbridge, housing accommodation improved and travelling facilities were gradually increased.

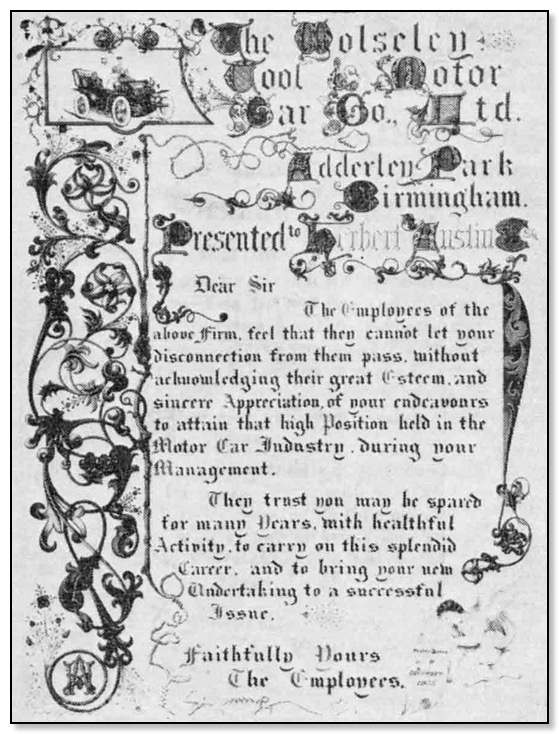

Had our founder followed his friends' advice, and bought a factory or site hemmed in by streets in the confines of Birmingham, development such as that which has taken place at Longbridge would have been impossible. An instance of this occurred in the first World War when the Government were able to buy two farms adjacent to the main Longbridge Works, on which were built the North and West Works for turning out munitions of war. But I progress too fast. On the 22nd December, 190-'), an Illuminated Address was presented to Mr. Austin by the Employees of The Wolseley Tool & Motor Car Company, a photograph of which is reproduced here.

The Wolseley Tool & Motor Co Ltd

Adderley Park Birmingham

Presented to Herbert Austin

Dear Sir, The Employees of the above firm, feel that they cannot let your disconnection from them pass without acknowledging their great Esteem, and sincere Appreciation of your endeavours to attain that high position held in the Motor Car Industry, during your Management.

They trust you may be spared for many Years with healthful Activity to carry on this splendid Career, and to bring your new Undertaking to a successful Issue.

Faithfully Yours

The Employees

As we all now know he did bring his "new undertaking to a successful issue." This Success not only brought to him the satisfaction and pride of a job well done, but it has meant a livelihood for tens of thousands of people and has increased the value of land and property in the neighbourhood. The process still goes on, increasing and multiplying on the solid foundations laid with so much wisdom in the early days.

First and foremost Herbert Austin was a from early to late he was "on the job," and he expected his staff to be available also, with no eye on the clock. It was well known that he could do all the types of work connected with a motor car, and in the early days he was not ashamed to take his coat off and demonstrate to a workman, who might seem a little confused, the right way to go about it.

He was plain of speech and in dress. He wrapped up very little in cold weather and wore Burberry double-purpose type overcoats. In the early days he always wore a black bowler, but in later years this was superseded by a black Homburg type of hat. But in Summer he favoured a Panama. He did not indulge in alcoholic beverages, neither did he smoke, and applicants for-staff positions were carefully scrutinized for evidences of these "vices." Too much colour in the cheeks, or stained fingers' were apt to bring the interview to an abrupt conclusion. Nevertheless he had a predilection for tasty food, and did not appreciate a menu that included plain roast beef, Yorkshire pudding and cabbage. Another of his aversions was for men with their hair parted down the middle.

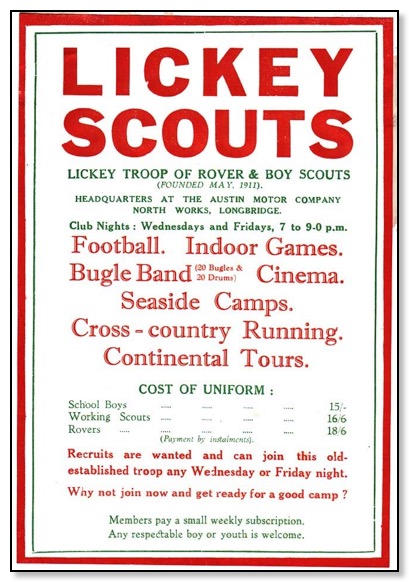

Lickey Scouts

Herbert Austin was always looking for way he could help the local community, and so he instructed Mr W A Howitt to form a Scout Group. This was setup in May 1911 and called Lickey Scouts. Meetings were held twice a week on Wednesday and Friday in North Works from 7.00 to 9.00pm. There were three sections to the group, starting with the School Boys, Working Scouts and Rovers. A small weekly charge was made and any respectable boy or youth is welcome to join. Payment for cost of Uniform could be made by instalments at (School Boys @ 15/- Working Scouts @ & Rovers @ 18/6).

After the great war the company paid for the Scouts to have their own purpose built Head Quarters at the top of Rose Hill opposite Lickey Church.

________________________

Charles Mobbs

Long before he had considered the wide range of employment open to a bright youngster, Charles Mobbs was coming to the Austin Motor Company. There as a member of the Austin Scout Group which he joined in 1914, he would study woodcraft and citizenship under the guidance of the Scoutmaster, Lord Austin’s secretary Mr W A Howitt. When the time came for Charles to find a job then, what more natural than that he should look to Longbridge, works for his livelihood!

Long before he had considered the wide range of employment open to a bright youngster, Charles Mobbs was coming to the Austin Motor Company. There as a member of the Austin Scout Group which he joined in 1914, he would study woodcraft and citizenship under the guidance of the Scoutmaster, Lord Austin’s secretary Mr W A Howitt. When the time came for Charles to find a job then, what more natural than that he should look to Longbridge, works for his livelihood!

'I started work here at the age of' 14 in 1918 and had a short spell in the aeroplane shop before going to the engine benches where I worked under the supervision of Mr Harry Austin. In those early working years I was on the move quite a lot, and before I felt like a change, I had been in No. 1 Machine Shop, No. 2, and on the North Works,' recalls Charles.

By then an experienced mechanic, yet feeling a little in a rut, Charles Mobbs left the works in 1935 to go to Bristol Street Motors, specializing in agricultural tractor work. 'it was interesting work, and grand experience, but a number of factors brought me back to Longbridge after three years away.’ he explained.

Servicing tractors involved a lot of travel and nights away from home - not very convenient for a family man and when, in 1936, his wife presented him with twins, Charles jumped at an offer by his old employers to come back on the aero engine section.

'War work on those engines kept me busy right up until the war ended, then I went on to inspection work on crankshafts,' he said. It was during the war, too, that his first connections with the firm were revived, for he represented the Old Scouts at the funeral of Lord Austin.

But another change of occupation was in store for Charles; he inherited a family business - a fish and chip shop in 1948. '1 wasn't too keen on trying to run it, and didn't know anything about the business, but I buckled to and went full-time into chip frying.'

After five years at the chip range however Charles longed to be back at Longbridge among his old friends and the work he felt more suited to. In 1952 upon the death of his mother he disposed of the family business and happily returned to the crank section on inspection work in No. 5 Machine Shop, where he is now contentedly doing the job for which he feels best suited.

He is a season ticket holder at Villa Park, and in his younger days was an accomplished back with the old Northfield Institute team, attaining league honours on several occasions. Now the mention of soccer is enough to bring a gleam to his eye-and the enumeration of the Villa’s unlimited good points!

At 59 Charles Mobbs has found the right niche-he is happy at work, happy looking after his trim little home; and although the word retirement does tend to crop up in conversation rather more these days, it is really nothing to worry about.

'I have two grand lads, both making careers for themselves in banking and salesmanship, and in January became a grandfather. I have some wonderful memories of the firm in its earliest days and believe I unblemished timekeeping record. When I leave it will be with no regrets at all.'

______________

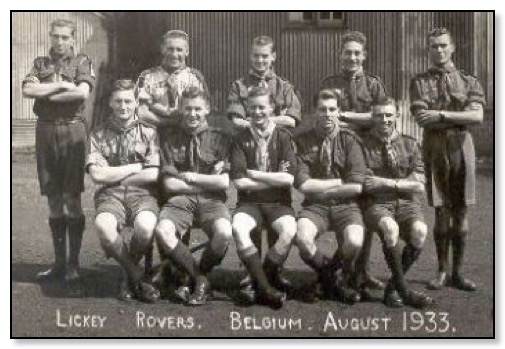

1920/1 Scout Fotoball Team with W A Howitt on the Left

With Austin Apprentices 1954

Memories of Herbert Austin by Mr Howitt

The Great Man was reviewing the correspondence of his firm's shipping department. He read the first letter, and his eyes narrowed. He picked up the next letter, and the next, glancing in quick anger at the bottom of each. “Who signed these letters ?”he demanded “ Send him to me!” Wondering, I summoned the gentleman concerned. As he came in the door Lord Austin observed dryly: “I see you have signed yourself as Shipping Manager.” The man began to explain,, Herbert Austin cut him short and threw the letters on his desk – a desk whose top was scarred by the heavy,- restless movement of its owner's thumb. Then with careful emphasis he said: “In future, please confine your signature merely to ‘shipping section’ . . . I am the only manager around here.”

A small incident, perhaps, but one which typified every-day life with a mechanical and organisation genius, ” The unfortunate “ shipping manager,” like many other men about Herbert Austin, probably regarded him as autocratic.

Never Dull

Of course, he was autocratic. He took for granted his divine right to lead while others followed and he took it or granted that those about him would unswerving serve the demands of his creative imagination without thought either of the hour or the effort entailed.

It is significant that his worker never failed to answer his demands. To know why is to learn one of the secrets of the foundation of his motor empire which this week end is celebrating its golden jubilee. Those who experienced life with Herbert Austin remember it as a switchback ride; exhilarating sometimes apprehensive, but never dull. It was always a race with time, Lord Austin himself setting the pace in little as well as great matters.

My own habit of typing documents with a space between each letter came under fire, because it wasted time. Austin even moved his own house from Erdington to Barnt Green in those early days because the journey to Longbridge had been wasting time. Even when he was riding to the station to catch the London train his energy would not rest. This was the time when the last of the morning’s letters could be dictated.

Once on the train out came his notebook and pencil and the journey always produced its quota of new mechanical ideas – plus quick, decisive sketches to make sure those ideas did not escape attention.

My first stake in the great adventure that was to become the mammoth Austin Motor Company of today was an application for job with the Wolseley Tool and Motor Company at Adderley Park Birmingham at that time was a city of cable cars, steam trams a two-way traffic. Herbert Austin as he was then had not long returned from Australia where he had managed the sheep shearing side of the business. Australia had opened his eyes to the need for swift, reliable transport in the land of opportunity.

A brief spell as temporary secretary to the man, who at 35,was already general manager of one of the largest firms in a pioneering industry which began for me an association which was to last 40 years.

Happy though he was at this time, Austin was impatient at his lack of final authority in the firm, and eager to become his own master. At a London board meeting of Wolseleys he was ordered “Wire Birmingham and halt work on this new process”

The board had decided that the cost of the latest innovation was too great. Austin sent not one wire, but two. One gave the order, the other reversed it. That was when he decided to launch out on his own.

Unlike many new companies, the Austin Motor Company was not built merely on hope and capital. Herbert Austin knew his way about engineering, and he also knew what he wanted. I first saw Longbridge on November 2, 1905 - my birthday -and it was snowing. With a few others, I had eagerly thrown in my lot with young Mr. Austin when he decided to set up on his own.

The night before I began work there, he drove me to his home and insisted on my staying the night. At least, he decided, he would have one of the staff present the following morning. With meat sandwiches wrapped carefully for lunch, we drove into Longbridge in Mr. Austin's Wolseley. Already a draughtsman was at work on the details of the first Austin car. The saga had begun.

There followed hectic days in which Herbert Austin’s energy went into top gear, and he was supremely happy. Inventions streamed across his memo pad and patents agents had to be found. Herbert Austin seemed to be everywhere. "A telegraphic address we want one," he said one morning. That of Wolseley’s was “Exactitude” and had been chosen by Mr Austin.

He paced twice across the office, the turned, his eyes mischievous. “That’s it, speed - speed - Speedily! “That’ll do. Now then what’s next ?” To this day the telegraphic address of the Austin Motor company is “Speedily, Birmingham.”

The First World War brought both triumph and tragedy to Longbridge in general and to the Austin family in particular.

The production by Austin's of an 18-pounder shell at a cost lower than had ever been thought possible was one of the technical victories of the war. It came near to creating a revolution in production in similar factories up and down the land, and on it rested Mr. Austin's hopes of achieving one of his few material ambitions, a knighthood.

With the end of the war, however, there merely came a very impersonal letter from the Privy Purse Office of Buckingham Palace. “Third class” it said in the top left hand corner, and went on: “Your name appears in the list of those who have been recommended to the King for the Order of the British Empire.”

It then requested Austin to fill in and return a form.

The proud genius was annoyed. He given his country much and there was much more he had yet to give.

He answered, “I could not accept any honour which does not allow me the title of a Knight.” Soon afterwards, he became Sir Herbert Austin.

Those shells caused alarm not only among enemy lines and (indirectly) in the Privy Purse Office. The landladies of flourishing village, too, were startled by them.

They discovered that Belgian refugee arm workers – their boarders – were using reject shell cases as money boxes. One tearfully explained: “I thought they were making bombs in my parlour.”

If the war, brought honour to Sir Herbert, it produced sadness, too. His sacrifice was his only son Vernon, a lieutenant in the Royal Artillery in the Royal Artillery, who was killed at La `Bassee in 1915.

Even as a preparatory schoolboy at Malvern Link, Vernon had been in love with the Army. His favourite book was “Deeds that won the Empire,” and his most persistent request: “Buy me a bugle !”

When he was killed, at 22, his mother asked for her son’s body to be brought back to England. It was exhumed and reburied at St Martin’s Churchyard, Canterbury, near the church Vernon had loved.

The ‘Baby’ Austin.

During the first four years of peace, Sir Herbert moved nimbly on to produce the first Everyman’s Car, the “baby” Austin Seven, which answered derisive criticism with record sales.

Austin had not only built a new car; he had also created a new market. Triumphs or no, he was little changed. His purpose was as unbending as his prejudices. Of these, tobacco and drink headed the list. Many a candidate for work with Austin was subjected to the great man's scrutiny for signs of either vice.

At the end of such an interview I would be asked: “Red in the face . . think he drinks ? " or, " I don't like him. His hair is parted down the centre.”

One unfortunate man came seeking a job as valet. I spotted him a few minutes before his interview with Sir Herbert His fingers were stained yellow. "Quick! In here," I whispered urgently. We got the man to the scullery and began working feverously on his hands. He got the job.

As each of the uneasy inter-war years passed, more and more honours were. bestowed upon Sir Herbert, the chief of which was his barony in 1936.

By that time the name Austin had become synonymous with reliability in road transport. And man who bore it was a legend, even in his own works.

His habit of making an unexpected visit to any part of the establishment made the legend live. If he saw a man fumbling a job he could never resist the temptation of growling: “I could do it better myself - and proving it.

Lord Austin did not live to see the end of the Second World War that followed so soon afterwards. Pneumonia

began an illness of months during which he directed the company from a room adjacent to his bedroom.

Every inquiry about his progress received a typical answer: I'm getting better. At 9 am on May 23, 1941 I arrived at his home as usual. His mind was as incisive as ever, dictating letters and giving directions regarding others. He signed the last of the morning's mail - a letter to his friend Bob Carlow, of Glasgow and I left at ten o'clock. Just over two hours later he was dead.

His death robbed the world of a determined, wayward and generous genius who helped thousands of individuals and many organisations. He asked one thing in return, loyalty.

But the Austin tradition lived on after the death of the founder. Lord Austin had a habit of being lucky as well as correct. And he confirmed both virtues in regarding as his successor Sir Leonard Lord, now head of the British Motor Corporation. Sir Leonard shares many of the dynamic qualities of his predecessor, not least of which is an impish sense of humour that enables him to wear his heavy responsibilities lightly.

He has taken the fortunes of the Austin Company on to new heights of achievement. But that sense of humour has remained. It is typified by the story he told at a recent dinner during which he was congratulated on his knighthood. “ Before I was knighted he said, " men who saw me coming in the factory warned one another: 'Get your head down, Jack here comes the boss . . . ' Now all that has changed. Now they say, ‘Claude, work for the Knight is nigh!’

To those who helped build an empire, there is more than an echo of Herbert Austin in those words !