EQUATOR TO THE ARCTIC CIRCLE EXPEDITION

In A

AUSTIN A40 Somerset MOX 656

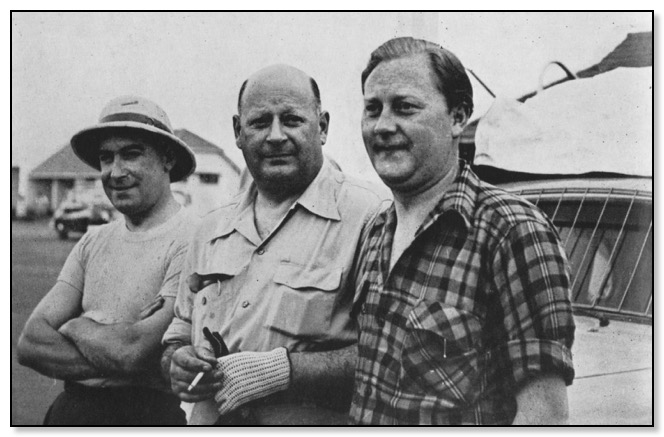

THE TEAM

Ken Whartton - Alan Hess - Ron Jeavons

My idea was to drive an Austin A40 Somerset from theArctic Circle to the Equator virtually non-stop and as fast as possible in order to submit it to extremes of cold and heat under actual and arduous working conditions. There are many types of test which may be simulated on the test bench, but the lessons to be learned from a high-speed run such as his can only be learned by actual practice.

The original intention was to start in the Arctic Circle on the North American Continent and run down the Alaskan and Pan-American highways to Quito in Ecuador and the run was planned from north to south for no better reason than that the phrase " From the Arctic Circle to the Equator " trips off the tongue more readily than " From the Equator to the Arctic Circle."

After a little thought, however, it seemed obvious to me that the drivers wouldn't be able to " take " Equatorial heat when they were tired, so I decided to reverse the route from South to North.

There was no difficulty about the northern part of the journey as the Alaskan Highway is a known quantity, but the southern section was full of imponderables and after three months of correspondence on the subject I had, reluctantly,to abandon the project because there are no through roads south of Mexico City since the governments of both Panamaand Costa Rica are holding back over their share of construction work on that end of the Highway in the hope that UncleSam, in desperation, will complete their roads for them.Instead, all they have to offer is a succession of barely penetrable tracks preyed on by brigands and in places pretty well impassable. Followed many weeks spent in exploring alternatives. The first and obvious one was to start the trip from Stanleyville in the Belgian Congo, cross the Sahara to Algiers, ferry across the Mediterranean to Marseilles and travel north through Europe, but this was no good because the Sahara is only a going concern in December and January and at that time of the year the Arctic section in Europe is definitely " out."

Any idea of penetrating behind the Iron Curtain on this marathon presented such refuelling uncertainties that this, too, proved impracticable.

There is a reasonable road northward beside the Red Sea and one might have started from Nairobi and kept cast through Abyssinia to Alexandria, but at this time there was all the trouble going on between Britain and Egypt in the Suez Canal Zone and it would have been folly to plan such a trip then through that territory.

Only one possible route remained and this entailed a hazardous crossing of the Nubian Desert where, since no roads exist, one would have to rely on native guides and one’s compass, but as this was the only alternative the obvious risk had to be taken.

It was therefore decided to start from the Equator south of Entebbe, on Lake Victoria in Uganda, and go north up the Valley of the Nile through Sudan and Egypt by way of Juba, Khartoum, Wadi Halfa, Assouan, Luxor, and Cairo to Alexandria. Then we should turn west along the North African coast to Tunis, catching the once-a-week ferry from Tunis to Marseilles and drive up through France to Strasbourg. We were to carry on north through Germany, using as much of the Autobahn as possible, by way of Hamburg to Grossenbrode where another ferry would be taken to Gjedser at the southern tip of Denmark, through Copenhagen to Helsingor, finally ferrying across to Halsingborg. The rest of our route was to be by way of Stockholm up the east coast of Sweden to Lulea from which point we should have to strike across country north-west into the unknown to the small township of Jokkmokk, just over the Arctic Circle.

Having settled for this route, timing became much more of a problem than I had expected. My Sudan contacts told me it was imperative that we should be through their country and into Egypt as early as possible in March as, if we were caught in the rains which start in early April, we should certainly get bogged down on the flooded black cotton soil with dire consequences. At the same time I learned from Sweden that March was really too early to expect to be able get north as far as Jokkmokk. After a great deal of research and study of meteorological records it appeared that there is only one week in the year in which it could be even remotely practicable to start this journey.

So here we were setting out on an expedition over the only available route during the only possible week in the in the year - and even then anything could happen.

As I have said, the object of the trip so far as the Austin Motor Company and Vacuum Oil Company were concerned was to learn as much as possible about engine and oil temperatures under actual working conditions in extreme variations of temperature, and to this end a variety of thermometers were fitted to the car in addition to an interesting array of prototype equipment. Furthermore, it was felt that the nature of this expedition might well capture the popular imagination and provide a good publicity story.

For me, I must admit that the real attraction lay in the fact that this was to be a journey of a type never previously attempted and one filled with many uncertainties and providing ample scope for resourcefulness and improvisation.

There are so few things left to do with a car that no one has ever done before and here was just such an opportunity to break new ground. The idea attracted me irresistibly.

Obviously the first prerequisite of such an undertaking is lot sit down and think; to try to foresee every aspect of it and decide on the order in which one should tackle the many problem involved.

When one is embarking on an unprecedented project, there is always the haunting fear that one's overlooked some vital but obscure factor and it's only by turning the whole plan over and over in one's mind, time after time, that such is to be avoided. Yet even this method has its drawbacks. One is apt through constant repetition to become too familiar with this ritual until one thought succeeds another automatically, habitually, until objective, creative consideration becomes atrophied.

Having obtained the " Go ahead " from Leonard Lord, I got down to the business of preparing the schedule for the trip and organizing the refuelling arrangements in collaboration with Guy Edwards, Vacuum's racing manager, and it immediately became evident that his company was keenly interested in the publicity angle because it was to be the first venture in Europe in which their newly-introduced fuel, Mobilgas, was to be used.

A meeting took place in London attended by the directors of Vacuum at which plans were discussed in some detail and I was delighted to discover the extent to which they were prepared to co-operate on the planning side in establishing refuelling depots practically wherever I asked for them, even though this was bound to involve them in much inconvenience and expense, because I was going to need the establishment of fuel and oil dumps in some outlandish spots.

One of the first jobs to be started and the last to be finished when organizing such an expedition, is the building up of one's schedule.

For this, I used a form similar to that which stood me in such good stead on my Round-the-World journey in 1951. This had nine columns. The narrow one on the extreme left recorded the day and date, the next one the name of the town, then came two sets of twin columns giving first of all scheduled times of arrival and departure, and then (left blank to be filled in during the run) actual times of arrival and departure.

Thus we could tell at a glance how we stood on schedule at any point and could calculate any required variation in average speed for the sections which lay ahead.

Next to these came twin mileage columns showing, first, intermediate mileages (i.e., distances between each of the towns) and then the growing (or total) mileage at each point.

Finally, on the extreme right, was a wide remarks column into which went all route-finding information, locations of frontiers, details of refuelling points, the names of any people we had to meet or contact en route, particulars of car or other documents required at any point, rates of exchange in the various countries, meteorological and topographical notes, addresses and telephone numbers of Austin, Lucas and Dunlop service stations on our route and all the other thousand-and-one essential points which had to be remembered.

The compilation of this bulky document calls for a great deal of research and patience, for it must be accurate in every particular - on this depends the success or failure of the entire expedition.

The A.A. supplied me with routes over the European part of our journey, but in some cases these conflicted with information gathered from local sources because one or the was concerned more with scenery than speed. That had to sorted out. But the A.A. only started at Marseilles, from which point on we were to use roads - although what they were going to be like in the far north was a bit unpredictable, even the A.A. not caring to commit themselves!

Over the African and Egyptian parts of our trip I was, so speak, out on my own.

I pestered all available sources for every scrap of information I could get and spent weeks poring over maps.

Every intermediate mileage I ultimately arrived at had to be checked and counterchecked before I dared insert it in the schedule and the average speeds between various points were adjusted in accordance with local conditions. It was a difficult but always fascinating process. I felt I had done the journey a hundred times over by the time our finally completed and still there were amendments and additions which continually became necessary in the Remarks column.

In its ultimate form, this document filled twenty-three foolscap pages, with three more pages at the end for official of our times of arrival /departure at key points and seven pages of maps, in addition to which local maps and street guides through large towns were pasted on the backs of pages to face their appropriate positions throughout the a schedule itself.

Quite an opus! But without it we might as well not have started and if it contained any inaccuracy it was likely to be more of a handicap than a help.

In addition to its obvious route-finding qualities, this bulky document possessed merits on the publicity side, for it enabled me to notify the editor of every single newspaper published in each town along our route of our anticipated time of arrival in his district when I sent him the advance story of our expedition with a map and photographs of the car.

There's nothing like " local interest " to interest locals ! By great good fortune, Horace White, a friend of mine, previously P.R.O. to the Government of Cyprus, had recently been transferred to Kampala to do a similar job for the Government of Uganda and his response to a probing letter from me was immensely encouraging.

He had no doubt that Sir Andrew Cohen, the Governor, would give us an official send-off, and he would be delighted to look after the Press publicity arrangements for me at the Equator end of the journey. This was good news indeed, because I already knew of his efficiency and realized we should be in good hands.

Austin's distributors in Kampala, some twenty miles from Entebbe, were equally enthusiastic, and again I was lucky, for Couperus, the managing director of Victoria Motors, was due to pay one of his rare visits to England and I was therefore able to discuss details with him personally.

So far so good, and I next set about tying up arrangements at the Arctic end through Hans Osterman of Stockholm.

But the bit in between the start and the finish was bristling with difficulties.

I expected resistance to the arrangements I should have to make for travelling through Egypt but, to my delight, these did not turn out to be too formidable. But it was altogether different with the Sudan. Every post brought me more warnings and discouraging forecasts of the complete impracticability of taking the route I'd planned - the only route which seemed to be available.

As ever, I relied on the Automobile Association to look after all the documentation necessary and, although this was more than usually complicated, Eric Ormonde completed all these arrangements for me without a hitch-but not without depressing me still further by sending me a number of horrific reports on what he described as the impossibility of following my route between Khartoum and Assouan, where no sane motorist dreams of driving, all cars travelling between one point and the other being taken up the Nile by river steamer.

Nor was I reassured in the least by similar reports reaching me from Mr. Stileman of Gellatly, Hankey and Company, who knows the territory intimately, and from Austin's distributors in Khartoum, both of whom seemed convinced that I was biting off much more than I could chew, and that I was attempting the impossible.

This sort of news would probably have deterred anyone of greater mental maturity than myself, but I have always believed that everything is impossible until someone comes along and does it - and it was really in this more or less desperate belief that I pushed ahead with my plans.

The first thing to do was to get the car and equip it with all the extras which I thought would be necessary. The acquisition of MOX656 was the signal for me to write to a number of suppliers asking their aid in providing – special equipment, and the immediate and enthusiastic response I received was one of those things which make projects of this sort so very much worthwhile. Indeed, I was nearly killed by kindness and was much embarrassed by the necessity to decline a great many offers of gadgets of whose material advantage to expedition. I was unable to share the conviction of their makers.

Even so, it was all, too clear that the car was going to be grossly overladen - a point which preoccupied the Dunlop experts no less than Austin's development engineers.

The spares we were to carry were kept down to the absolute minimum and yet they bulked some 10 cwt., and keeping the weight as much to the rear of the car as possible in order that it would be manageable on the icy roads up north proved a major problem.

Dunlops were providing us with sand tyres which we knew we would have to deflate to the lowest practicable pressure and I established a halfway-house with the Austin distributors in Copenhagen where we were to exchange these for snow tyres, at the same time changing over to Arctic equipment and Arctic oil, and where, in addition, the drivers sent parcels of warm clothing to replace the tropical equipment with which they were to start the trip.

One additional item which was sent to Copenhagen to await us was a case of self-heating tins of soup, similar to that used by the Everest Expedition. This took some getting and every official source I tapped proved useless, but in the end it was obtained for me by our own grocer in Worcester!

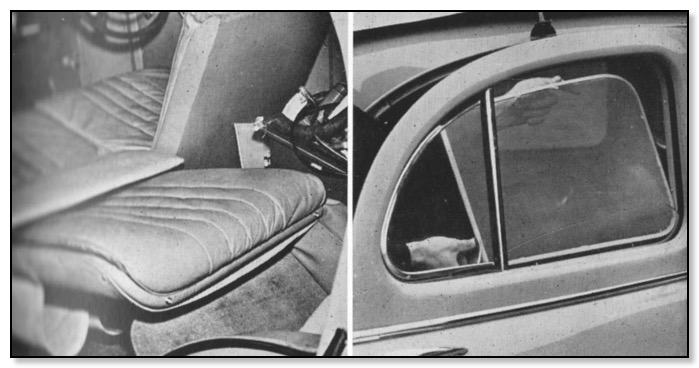

Reclining Passengers Seat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mesh Fitted To Side Windows

Cutting though the multifarious items of special equipment called for and subsequently discarded in an effort to save weight, the car was finally fitted with, among other things, a specially strengthened Victoria roof rack which was ideal for our purpose, and did a wonderful job; a new type of Triplex windscreen called Sundym, shaded green at the top and down to clear by the time normal range of vision was reached – this too, was worth its weight in gold and saved our eyes a great deal of strain in the desert; one of those increasingly popular plastic oblongs standing up at right angles from the bonnet to deflect the airstream off the windscreen and keep it clear of flies. This little device is worth a special mention because it served us so well. Not only did it deflect flies and months from our screen, but also sand when we had to follow other vehicles, and even snow up in the north; so that we never had to use our windscreen wipers at all, except after using the Trico Folberth screen spray-when even this wind deflector found itself unable to cope with the impenetrable clouds of dust which engulfed us on some occasions.

Another unorthodox fitment which was to prove invaluable was a shockingly expensive and very powerful siren-totally illegal-but oh, so useful!

Stout towing hooks were fitted to the chassis fore and aft, a sump-guard in the form of strong steel skids and, as we expected to have to travel really fast through Europe if we were to average over 6oo miles per day from start to finish, including what we knew was bound to be slothful progress through the desert, the Lucas Company provided us with specially powerful head lamps and fog lights.

A hand-operated spotlight was added on the driver's side and two shovels were fixed in front of the bonnet (the legend " Yours " being painted on the handle of one, and " Not Mine " on the other-which shows the nice spirit existing between Ken Wharton, Ron Jeavons and myself from the outset!).

I could not have been more fortunate in my companions. Wharton is too well known and his driving prowess too out-standing for me to have to introduce him to most of my readers, but I might perhaps add for the benefit of those who may not normally be interested in motoring that, although only 38 years of age, he has attained the highest pinnacle of fame in every sphere of competition driving. He was British Trials Champion in three successive years, I 948-1950, and Hill-Climb Champion in 195 1 and 1952. He holds the records for Shelsley Walsh, Prescott, Bouley Bay, Rest-and-be-Thankful, Lydstep and the difficult French hill, Col Bayard. To add to the score, he has thrice won the Tulip Rally, and was also the victor in the Lisbon Rally in 1950. He was the first British driver to finish in last year's Italian Grand Prix at Monza, and immediately after his return from our expedition he collected fresh laurels by winning the principal race of the day at Goodwood on Easter Monday at record speed in the B.R.M.

I knew all about him, of course, as a driver, but what I had not expected was that he would exhibit such a lively interest from the very start of our project and offer so many helpful suggestions in connection with the equipment of the car.

Jeavons, although only 34, is an old, tried and trusted partner, having been with me in 1950 at Long Island when Goldie Gardner and I attacked Stock Car Records there and later that year having been one of those who shared the driving with me at Montlhery, outside Paris, when we made our 10,000 miles in 10,000 minutes' run, and finally having partnered me in our drive Round-the-World in three weeks in 1951.

Although they have in common a love of motoring adventure, it would be hard to find two men less alike in every other respect. Jeavons blond and impassive, Wharton dark and volatile. Jeavons always content to take things as they come, Wharton impatient to make them happen his way. Jeavons the reliable, plodding, text-book type of mechanic, steeped in Austin practice; Wharton quick, opportunist, original, a staunch believer in the merits of unorthodoxy.

Not only in theory but in practice, too, they were an ideally ill-assorted pair who got on splendidly together.

The kind of thing which helped to keep us on a level keel temperamentally during the run itself was that little business, that trivial but oh, so important little business, of the ring-spanner.

Jeavons had borrowed some special tools from the works and had signed a receipt for them, pledging that he would take care to return them all.

Wharton found among them a ring-spanner which he coveted.

Came a time when Jeavons missed this tool out of his kit. Not unnaturally Wharton fell under immediate suspicion nor did his replies under interrogation do much to establish his innocence, especially when he ended his denials by offering to " flog " one of the car's accessories to Jeavons in exchange for the missing object !

I should say that ring-spanner changed pockets a dozen times throughout the trip as one of them "acquired" it from the other, the dispossessed always complaining loudly of the dishonestly of his companions.

Jeavons, of course, was the final victor, justice sometimes being what it is believed to be. I'm sure Wharton always intended, really, that it should end that way; and although all this may appear very childish when written, I do assure you that it had a very real value at the time, for when one is cooped up for days and nights on end with one's fellow beings, one's thankful for anything which lightens the atmosphere.

I wonder why it is that people get on one another's nerves, whereas animals never seem to be similarly afflicted when herded together ?

In working out our schedule I had provided for stretches of 350 miles between refuelling points and had decided to carry on the roof four jerricans of petrol as an emergency ration. As we were also to carry sand-tracks, a jerrican of water, two additional spare wheels, a large blow-lamp which could be used as a flame-thrower against snow-drifts and an Aldis lamp whose purpose I will describe later, in addition to our 10 cwt. of spares, a nylon tow rope, de-ditching gear, all our clothing, food flasks, etc., it will be appreciated that the boot was soon going to be filled to overflowing and much weight would have to be carried on the roof. This was the last thing we wanted and it was Wharton who suggested that we could save roof weight by dispensing with one or possibly two jerricans if we utilized odd nooks and crannies in the boot for additional tankage. This idea was promptly acted upon, giving us a tank capacity of 18 gallons, and as time went on other modifications were made, including a fitment for one of the spare wheels on the outside of the boot lid.

After the interior of the boot had been adapted it was found that it would still accommodate not only the second spare wheel but also both jerricans of petrol, and this left the roof rack free for less weighty but no less bulky objects.

The nearside rear seat and squab were removed and a sling for the jerrican of water was substituted for the latter, while the back of the nearside front seat was made to let down flat to form a bed. On the run, unfortunately, we found we had so much clobber in the back of the car that we were never able to avail ourselves of this luxury, but it remained a good idea in theory.

Over the windows were fitted removable close-mesh wire gauze frames which would let in air but keep out insects, and these were to play an important part later on, although in a totally different role.

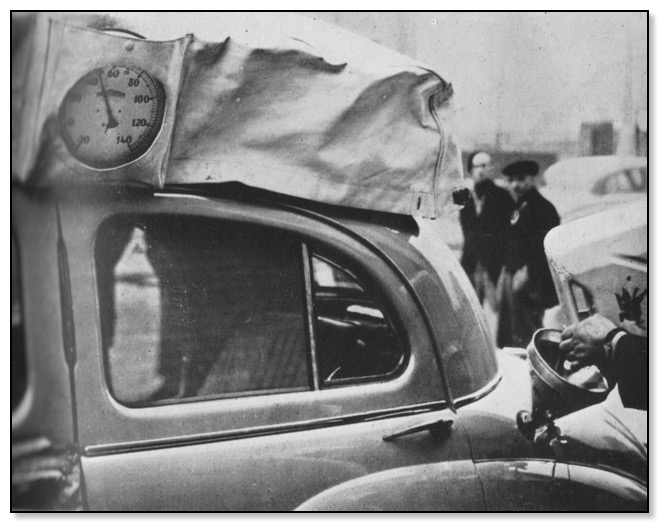

The large external thermometer was fitted in the tarpaulin to provide

a photographic record of outside temperatures at refuelling points, or other times.

An under-bonnet inspection lamp, four fitted pockets for thermos flasks behind the navigator's seat and a map-reading lamp fitted to the outside of the lid of the glove box were other items worthy of mention, while, finally, the whole of the front of the car was finished off with a matt paint to eliminate reflections and rather colourful maps of our route were painted on both the front doors. The drivers each went into his own interpretation of the word " training " about the only factor common to all three being a determined effort to keep " on the wagon " until the trip was over and we then set about having all the unavoidable inoculations which seemed to cover every scourge known to medical science.

We deployed our personal clothing with some forethought, sending our warmest stuff to await us at Copenhagen and each sending a respectable outfit to Stockholm to be there when we should arrive back from Jokkmokk, while we knew we should also each have to take a decent suit with us to Entebbe as on the eve of our departure I planned a dinner there for the Governor and local notabilities and Press and all those who had helped us during the final stages of our preparation. All this strained our sartorial resources to the uttermost and what we should wear immediately on our return home should we fail to complete our journey was a thought none of us dared to entertain.

Chapter TWO

On 19th February MOX656 left, crated, by sea for Mombasa, whence it was to be taken by rail to Kampala to await our arrival on 11th March.

A week after the departure of the car the Vacuum Oil Company gave a Press Luncheon at the Dorchester House, Park Lane, to announce the forthcoming expedition. This was presided over by J. C. Gridley, their chairman, who, with his fellow-director Miles Reid, welcomed Leonard Lord whose presence, my co-drivers and I felt, set the seal of his personal interest in our plans.

By this time I had already paid a brief visit to Entebbe to tee-up the final arrangements there having flown out by Comet on February 3rd, returning three days later.

This literally flying visit had also enabled me to meet contacts in Cairo and Khartoum when the plane touched down there to refuel and during these brief encounters I was able to achieve more than could possibly have been done in months of letter-writing.

I hope I have not conveyed the impression that all the preliminary arrangements had been undertaken single-handed by myself during the preceding weeks, for a tremendous amount of hard work had also been put in by Guy Edwards and, on the advertising side, by his colleague Peter Bancroft, and my own colleague Sam Haynes, but the preparations for the actual driving part of the whole project were essentially my own preoccupation.

In addition, Caldwell in Khartoum and Neville Flower in Cairo had to work really hard to obtain permits and passes for us, without which we could not proceed through the Sudan or Egypt.

Peter Newell, of Austins, made himself responsible for the visas for Wharton, Jeavons and myself, and also for getting the currency I asked for from the Bank of England. The sort of' silly thing which crops up to cause delays was the insistence of the Egyptian Government that we furnish them with positive evidence that none of us was a member of the Jewish faith.

After a number of possible methods of satisfying them had been discussed and rejected some because they were considered frivolous, letters were obtained from Church of England parsons testifying to our faith and all was well.

At this time, too, concerns entirely outside the normal orbit of motoring were giving valuable help. B.O.A.C. issued a Crew Notice instructing their pilots to watch out for us during the desert crossing. This took the following form:-

CREW NOTICE

AUSTIN MOTOR COMPANY'S EQUATOR/ARCTIC EXPEDITION

An Austin Motor Company team of three intend to drive an A40 from the Equator (at Entebbe) to the Arctic Circle (Northern Scandinavia).

They will leave Entebbe at 0800 hrs. on 17th March, 1953. The route they will follow is displayed on a chart in Flying Staff Administration Office.

The main points on the route are Kampala, Juba, Malakal, Kosti, Khartoum, Berber, Wadi Halfa, Assouan, Luxor, Assiut, Cairo.

A schedule for the journey as far as Cairo will be placed in the First Officer's folder.

If a real emergency arises signals will be made in the hope of attracting the attention of aircraft.

They carry no radio and their signals will be as follows.

(a) At night a beamed light directed towards the aircraft;

(b) In daylight an oil fire (dense black smoke); and

(c) White arrows on the ground near the car. If the arrow points towards the car it means that medical

supplies are urgently needed: if the arrow points north it indicates that water is urgently needed.

You are requested to keep a particularly sharp look-out during the period of the car schedule, and should any of these signals be sent, signal the information to your Control Station. Should you receive a message from the ground stating that the car is in genuine difficulties, then you are authorized to make whatever search you may consider at your discretion to be necessary.

(Signed) W. B. HOUSTON.

Origin: Fleet Manager,

February 13, 1953.

Another firm, Pest Control (Sudan) Ltd., who operate a fleet of helicopters in the Sudan, similarly instructed their pilots.

Offers of help poured in from all quarters, including the provision of a couple of torch screwdrivers from John Clennell & Co., a number of Smog anti-mist cloths from Wayte Smith & Co., even a supply of tissues from Kleenex and, perhaps most acceptable of all, the weatherproof binding of our Schedule and Log by Messrs. Kalamazoo.

It was to enable us to signal to B.O.A.C. or Pest Control aircraft that I had borrowed from the Aldis Co. one of their Morse-signalling lamps and as none of us knew the Morse Code I cast around for a means of getting this done out in luminous paint on a black background for use at night. The obvious people to ask were Smiths Motor Accessories and my good friend Frank Hurn immediately complied. By the way, I had collected this lamp personally from John Aldis at their works and was immensely impressed by a large board outside proclaiming: " Firms' Representatives are welcomed here. Otherwise we might miss something."

That was that, but good as it was it was by no means enough, I felt.

From all I had learned of the kind of trip this was to be, I was convinced that nothing must be left to chance and that I must face up to every eventuality, however macabre. And so it was that I asked Austins to take out special insurance policies for each of us for £5,000; then I set my personal affairs in order-in so far as such chaotic matters may ever be regularized-writing a lengthy and faintly melancholy letter to my brother-in-law, outlining just how materially my failure to return might be expected to benefit my wife. From all this, the conclusion was inescapable that I should be a much better investment to her dead than alive, a humbling but comforting consideration.

I must admit that I was at pains not to reveal to Diana just how grim a prospect our impending journey presented. I don't call this duplicity on my part although I was troubled by the thought that I was not being honest with her.

She, bless her, was wonderful about it all, as she always is on these occasions. I must have been a rotten companion for her for months before we left, for I was oppressed by a multitude of detail which all had to be made to dovetail somehow, a process calling for intensive concentration, so that I tended to become absent-minded about those vital domestic concerns the sharing of which forms the foundation of all happy households. I grew absorbed, morose and intolerant and behaved with a selfish disregard of others, I can see it all now, in retrospect.

And through it all, Diana helped and encouraged me and I put up a brave facade of courtesy to outsiders behind which I was glad to hide.

This she did because she could see with what a complex mass of itemized organization I was wrestling. Whether she would have entered into the spirit of those days quite so wholeheartedly if I had been frank with her about the perils which lay ahead of us, I rather doubt.

Bit by bit, the elaborate jig-saw of our arrangements became built up into a more or less recognizable whole but not without last-minute alarms, lots of them.

Just as I thought all my refuelling arrangements were completed I was thrown into a minor panic by Hinchcliffe, who, in the course of a talk on his recent Sahara crossing, divulged that through much of the thick sand he had only managed to average 6 m.p.g. I knew that I'd cut down the petrol we were carrying to very near the bone for some of the longer stretches and I was acutely worried by this revelation. But the Vacuum boys came to the rescue and arranged at short notice to have emergency supplies available for me at four vital points-Kosti and Abu Hamed in the Sudan, and at Assouan and Assiut in Egypt.

This was a load off my mind and as by now we'd received all the visas and currency I felt we were pretty well all set, but I wouldn't go so far as to rate our chances of completing our journey on schedule any higher than 20 per cent. for and 80 per cent. against, because there are so many unknown quantities to be faced, both in the desert and after leaving Lulea in the north, and even the known difficulties were indeed so formidable.

Then, five days before we were due to leave, I had a letter from Keith Baldry, the Standard Vacuum Company's Nairobi representative who had flown up to Entebbe to meet me a month before, saying: " It may be of value for you to know that as far as the rains in East Africa are concerned, the worst seems to have happened-they have arrived some four weeks early. In Nairobi we have already had 24 hours of heavy rain, but as yet I have no information about Kampala. I am, however, expecting to receive some within the next two or three days and if their rains are also early I will notify you by wire."

I heard no more and although that might have been construed as good news it did nothing to assuage my acute uncertainty.

On the morning of March 9th, the Lord Mayor of Birmingham received the three of us at a Press conference and wished us luck, saying that he would watch our progress with interest and asking me to cable him on arrival at Jokkinokk.

One of the last things I did before leaving was to make a number of purchases from a local chemist. These included everything I knew we should need, in triplicate, and a number of things I thought we might find useful. Into the latter category came some boxes of Macleans throat tablets. These were a frankly speculative investment, based on the assumption that our throats would get dry through dust; had I but known it they were destined to play a much more important part than just that and I really believe that I am not overstating the case when I say they probably saved my life

Bill McClure and his colleague Freddy Gillman, Public Relations Officer (P.R.O.) to British Overseas Airways Corporation, had been tremendously helpful to me all along. It was Gillman who indirectly had arranged for the Crew Notice to be issued and who had, also helped me to fix arrangements at Entebbe Airport for the Governor of Uganda to see us off when we started and who, furthermore, had enabled me to arrange a refuelling point at the Sudan Airways station on the White Nile at Malakal in Southern Sudan and even to lay on some iced champagne to be awaiting us there. What a man! And it was Gillman who gave us a cheery send-off luncheon at Heathrow on March 10th, at which we were delighted to see Sir Miles Thomas, who had only flown in that morning from the Caribbean, but came to wish us God-speed and accompanied us out on to the tarmac to see us into the Comet that was to take us to our starting point.

Among the sheaf of good luck telegrams we received at Heathrow was one from the Lord Mayor of Birmingham surely a very graceful gesture on his part.

During my previous Comet flight to Entebbe I had sat with Humphrey Bogart as far as Rome and it was music to my ears to hear an American who was so obviously "sold" on the merits of the world's first jet airliner. " Gee, what a ship," he kept exclaiming, " we've got nothing like this."

This time it was a British actor who was the star of the trip, Sir Laurence Olivier. At Rome the airport was thronged with his fans and cinematographers went into action in a big way, as, rather nervously I thought, he descended the rickety steps to terra firma.

If any Comet flight can be termed uneventful, this one was-apart from the fact that we were half an hour late leaving Rome because of a strike of ground staff there, but picked up this time by cutting short our subsequent stops at Cairo and Khartoum by a quarter of an hour each, arriving at Entebbe punctually early the following morning.

I was glad for Wharton's and Jeavons' sake that we crossed the desert in the dark, for on my return flight from Entebbe a month before I had flown by Hermes which made that part of the trip in daylight, and I must admit I'd been more than a little daunted by the interminable miles of trackless wastes we flew over hour after hour and which I knew we were to motor across a few weeks later.

Entebbe was bathed, as ever, in hot sunshine and we were met on arrival by Hugh Dawson the Station Commander, and Denis Lloyd, East African Airways Corporation commercial manager, with both of whom I'd formed a more than business friendship during my previous visit and who were flat out to do everything possible to help us and bring their Station into the picture of our expedition.

Bristow, Vacuum's Uganda manager, was also there to meet us and took us with our baggage to the hotel, and we'd not been ensconced very long before Couperus arrived with the A40 he was lending us as a runabout for the week we were to spend finalizing our arrangements for the start of our trip, for Kampala is 21 miles away and obviously we were going to need personal transport.

What we should have done without this car I can't think, for we were continually ferrying back and forth and we soon found there was much more to do than we expected. We had all looked forward to this week as an opportunity to rest and condition ourselves for what lay ahead, but this was not to be and we were kept hard at it right up to the "off."

The first thing we discovered when we got into Kampala later that morning and were able to take the car out from Victoria Motors to test it was that it was running rather hot. The thermostat had been removed at Longbridge at my request but we felt, and this was subsequently confirmed by Bristow, that too heavy a grade of oil had been prescribed and this was duly adjusted. In a further effort to aid cooling we filed down to about half its normal width each lateral strip of the radiator grille, covered in the aperture between the top of the radiator and the front cowling so that the air that came in was scooped into the right channels and rather crudely made an air vent on either side at the back of the bonnet for hot air to get out.

These measures did the trick and from then on we had no more overheating troubles.

The staff of Victoria Motors who carried out these jobs were full of zeal and made many valuable and practical suggestions which they proceeded to implement for us and every job they undertook was carried through magnificently.

Remembering what I had learned before starting of the likelihood of birds, dazzled by our headlamps, starting up to late to avoid crashing into them or our windscreen, we fitted guards to protect our frontal glass and while all these things were going on I went off to see Horace White and do some necessary shopping.

So far as I can make out shopping in Kampala, apart from foodstuffs, centres around drapers' stores and it was there that I procured everything from raffia seats (which have a notable anti-sweat value) to essential hardware such as tin-openers, paper cups, cutlery and a fascinating gadget which delivers either salt or pepper or a mixture of both at the twist of a knob.

It was a good thing that I also bought some sun-glasses, for our consumption of these during the journey was quite phenomenal as they continually got lost or scratched or broken and repeatedly had to be renewed.

As time went on I got the very firm impression that even our best friends in Kampala did not really believe that we should succeed in what we were starting out to do, while strangers who could not be expected to realize how seriously we were taking the whole thing did little, and in some cases nothing, to hide their scepticism.

I shall never forget the visit I paid with Couperus to Duffield, editor of the Uganda Herald.

He is an expert on Africa, and he as good as told me that I was sticking out not only my own neck, but those of Wharton and Jeavons, by undertaking such a foolhardy enterprise and ended by assuring me of his personal conviction that we shouldn't even get as far as Khartoum.

"Up to Juba," he kept saying," you'll be all right, but after that anything can happen and no one need ever know."

This sort of talk from some people would not have worried me particularly, but I must admit that I felt bound to attach importance to such sentiments coming from a man of Duffield's wide experience and obvious sincerity.

If I were shaken I tried not to show it. Our plans had advanced too far now for retraction and the best thing to do was to put a good face on the situation and press on.

I didn't tell Wharton and Jeavons all that Duffield had said, but I did intimate in what I hoped sounded like an off-hand manner that we were not expected to get as far as Khartoum, at which Ken Wharton remarked on the coincidence of the name which, he thought, might alternatively be spelt CAR-TOMB.

The hotel at Entebbe was full. In addition to the usual crowds there was an incursion of film folk from the Ealing Studios on their way home from making a sequel to the film " Where No Vultures Fly," which, sooner or later, is due to be released under the title " West of Zanzibar."

They were a cheery bunch, but we really hardly got to know them because we were so busy, so that we were particularly touched when, the day we left, we received a telegram from them, despatched just before their own departure the day before, wishing us luck on our trip.

Attached to these movie men, was a White Hunter who'd been on location with them who took a lively interest in our plans-a "clinical interest," he called it-and, learning that we were unarmed, presented me with a frightening-looking panga.

Also in the hotel was a young super-salesman on safari from Nairobi who overwhelmed us with gifts to add to our equipment made by various firms he represented. The idea was that he would show the concerns back home how much more "on the ball" he was than they were, by cabling them after we had triumphantly concluded our journey, pointing out that, solely due to his personal enterprise, they could claim part of whatever credit might be due! All this would have had more value to us if only his wares had been appropriate to our needs, but unfortunately they were not, with the result that they merely cluttered up still more the already drastically restricted room inside the car.

But he was so nice about it all that we simply hadn't the heart to turn him down flat. The morning of March 16th was spent in loading the car. This was no haphazard operation, for logic dictated the procedure. Those spares most likely to be required were on top and near the front in the boot while the parts we thought would not be wanted were underneath and at the back.

All the electrical spares were kept together (and that included even such items as spare bulbs and batteries for our hand-torches) while other groupings included carburation items, suspension spares, and so on.

In addition to all this, we tried in so far as it was possible to maintain a balance of weight in the final distribution.

It was while we were preparing to stow away our freight and had it all unpacked and laid out in Kampala that we came upon an envelope in with our spares which, when opened, gave us a surprise. All it contained was a card on one side of which was a weird and wonderful pastel drawing of the bonnet of our car in a forest of horrific Disney-like trees of sinister aspect and on the back the well-known " Ghoulies and Ghosties " prayer, with a good luck message for us. This had been executed by the Export Packing Department back home, and we were delighted by their interest in our trip which it showed.

At last this lengthy but important task was completed and we felt we'd made a good job of it.

We drove MOX in from Kampala to Entebbe and knew that we were all set for our start the following morning after the farewell party we were giving that night.

Here I must break off to say a word about Entebbe's lake flies. The first I knew of them was when I looked out of my window one morning and saw a dark cloud of insects hovering over a hedge in the garden. A purposeful little dog went prancing down the path right through this cloud and I was amazed to find that, despite his undoubted aroma, the flies were not diverted from their apparent interest in the hedge.

The activities of the day drove this from my mind, but when night fell I had every reason to remember it, because (countless millions of these flies invaded the hotel and formed a cloud round every light.

The flies don't bite and don't do any harm, but they are an intolerable pest. It appears they live in the mud at the bottom of the Lake Victoria and at certain phases of the moon emerge and come up through the water to infest the town.

You have literally to fight your way through them and when I entered my bedroom, the moment I switched on the light the room was full because the wire gauze had come away from the window at one point, leaving a small gap.

In my bathroom was a Flit gun, the reason for which I had wondered at, because both Entebbe and Kampala are quite phenomenally free from insects. Now I knew. Beating off the invaders I made a dash for the Flit gun but, of course, it was empty.

An S.O.S. to the management and an army of native boys came up and flitted wildly, but by this time the flies were everywhere, in the bed, in the wardrobe, and even, miraculously, inside my closed suitcases.

The next morning the hotel corridors were thickly carpeted with the dead bodies of these tiny insects which were swept up into huge piles and taken away in buckets.

There is a singularly defeatist attitude to this nuisance among the people of Entebbe. " Nothing can be done about them," one is told, " and anyhow they don't do any harm, they're just a bother." All of which seemed a masterly understatement to the three of us.

The visitations from these insects last some days and I wondered what they were going to do to our dinner party that night.

They were there all right, in their millions, but it didn't really matter. The management switched out the centre lights over the tables and we sat down surrounded by a number of small clouds clustering round the wall lamps and I think it may safely be said that once the proceedings started the flies were forgotten and everyone enjoyed themselves. I was fastened on to early in the evening by Jack Hayes, Uganda's Traffic Superintendent, who seemed to perceive in me a link with home as he took pride in telling me that he had sat next to Dodd, Chief Constable of Birmingham, through Police College, and I was charged to deliver personal greetings for him on my return. Arising out of this, he offered us a police escort to by-pass Kampala on our way from the Equator the next day and topped this off by saying that if, on arrival at Gulu, there were any spares we wanted we could get through to him direct from his private wireless station at Gulu and he would fly them out to us within two hours.

This was typical of the spirit of co-operation and interest we found everywhere and it was a great pity that the annual Prize Giving at the Mackerere College should have clashed with our dinner and so prevented the Governor or the Mayor of Kampala from being with us, but most of the other important officials turned up, and in particular we were glad to welcome the various representatives of Victoria Motors and the Uganda set-up of Vacuum as well as the local Press.

2

Chapter THREE

We were up early the following morning as we had to leave the hotel by 7-30 in order to get everything under control at the airport before the Governor was due to arrive at 8 a.m. One of those who'd come to Entebbe specially from Nairobi to help us and see us off was Harper, the East African representative of Austins who now, at the last moment, fclt anxious for our safety since we were proposing to make our journey totally unarmed except for the panga given me by the White Hunter, and pressed upon me his own small revolver with a few rounds of ammunition, all neatly done ul) in a little waterproof bag. " Sling it away if it's a nuisance to you," he said; " it doesn't matter if I don't get it back, but I do think you ought to have it." Had I slung it away it would not have become the embarrassment to me which it turned out to be-but that's another Story.

When we got to the airport all the station officials were already " on parade," likewise the Vacuum staff, a sprinkling of " still " and movie cameramen and a number of local inhabitants and other well-wishers into whose lives we were bringing such an unaccustomed episode. Punctually on the stroke of eight the Governor's car arrived and he greeted us without any of the acerbity which might have been excusable at such an early hour. He had a good look round the Austin and seemed particularly fascinated by our new type of windscreen; he then autographed the bonnet of the car, shook us by the hand, wished us bon voyage, and waved us off.

During my previous visit I'd done the 6o miles from Entebbe to the Equator with Couperus and had been impressed by the many 10ft. tall ant-hills of red earth we passed and appalled by the dust on the Kampala-Masaka road. Apart from the dust the road itself is a pretty bad one with deep corrugations and ruts and pot-holes, particularly where it passes through swamps which flood it from time to time.

But even the dust has its compensations, for here it is of terra-cotta and clinging to the lofty foliage on either side of the road it gives this a kind of shot-silk effect of deep green and ruset which is beautiful beyond description.

We soon found that a definite window drill was called far and the moment we saw a vehicle ahead of us or approaching, up would go the windows until the inevitable cloud had subsided and we could get some air again. Strangely, there was a tendency not to be quite quick enough at this when coming up behind another vehicle to overtake. I suppose this was because you couldn't see the vehicle itself, but we found we were continually caught out on these occasions by leaving our window drill until a bit too late.

On we went, through Mpigi, past the tiny cotton plantations between countless banana trees with their tattered foliage hanging motionless in contrast to our own jolting, jostling, bumping progress-rattling on until at last we could we from our speedo-trip that we must be getting close to the line.

At the Equator itself we found quite a crowd-the ubiquitous Vacuum characters having gone straight there Kampala to affix their flying red horse sign immediately beneath the official board marking the line of the Equator. The party also included a few more photographers and, of course, a band of curious natives, one of whom was a ten years-old girl accompanied by her two children.

Quite frankly, although we felt under a deep debt of gratitude to all the Vacuum boys for their untiring help, we did get a bit oppressed, at times, by the omnipresence of their flying horsepower sign which had become known to us, more or less as affectionately" McGinty's Bloody Goat."

I did feel now that it was a bit of a mistake for it to be placed so prominently immediately under the Equator-board as I feared that the photographs showing it there might cast some doubt on the authenticity of the board itself-but that's by the way.

Still I couldn't really beef at the resourcefulness shown by Bristow and his gang because they really had turned cartwheels in an effort to meet all my exacting refuelling requirements and must have gone to an immense amount of trouble. Indeed Bristow himself had become so obsessed by the whole thing that he even dreamed about it-for his wife told us that he woke her up one night muttering " Hess ... a lot of ruddy nonsense . . . ! "

We arrived at the Equator at 09-50 hours and after submitting to all the photographic formalities required of us, set off again 20 minutes later at the real start of our expedition.

Ken Wharton was now at the wheel. I was beside him as navigator and Ron Jeavons was trying to keep all our things in the back of the car in position despite the jolting they were receiving over the ghastly road.

On the outskirts of Kampala we met up with our police escort, comprising a European officer on a motor-cycle, accompanied by two native policemen similarly mounted. Couperus was there, too, with his own car and without stopping we fell into procession with the police officer in the lead followed by our car, the two policemen as outriders and Couperus bringing up the rear.

The plan was that the police would take us round Kampala to save us going through its congested streets and set us on the road for Hoima and Masindi. Up to this point we'd been going along very nicely between 40 and 50 mph., but now our leader slowed us down to half that speed, although we were by no means in the town, and as we were anxious to get to the ferry at Atura more than 200 miles away in daylight and since we knew we had some bad roads ahead of us, this didn't seem to be much good.

Ken sounded his horn impatiently and the police officer looked round but went on again at his funereal pace. A moment later we drew alongside and I beckoned to him to speed up a bit and this time he did-in fact he went so fast that he overshot a turning he meant to take and crammed on all just as he was passing over a patch of oil. The resultant skid nearly threw him off under our wheels and shook him so badly that he never again exceeded 15 mph., and point with Couperus at the back could see we were reaching bursting point with impatience so tactfully streaked away ahead and we tucked in behind him, leaving our escort behind.

A few minutes later he stopped, leapt out and waved us past. Now at last we were out on our own.

We had left Kampala 15 minutes late due to the slowing effect of our well-meaning but somewhat inept police escort, but by the time we had covered 90 miles and reached Butemba we were 15 minutes early, having averaged 41 mph. from the Equator and the thermometer inside the car was registering 100 degrees Farenheit.

We got to the ferry at Atura more than an hour ahead of schedule and the crossing took us only 20 minutes. A few miles further on we saw an Austin Countryman coming towards to us and this pulled up as we passed and we got the impression that it turned and followed, although we couldn't be sure

because of our own dust cloud.

Just before reaching Gulu we stopped momentarily and the other car came up, whereupon we discovered that it had mounted on the back of it a large banner reading "Austin Project-Follow me." This was Higginson, another of be Bristow's men, who had not expected us to be so early at the ferry had come to lead us into Gulu, but as it turned out we’d led him until we'd stopped. From then on, to save his face, we let him go in front and endured his dust!

During the journey between the Equator and Gulu we'd made two interesting discoveries, the first that everything we had in the eatable line was likely to melt before we could consume it and the second, that Pepsicola can be quite palatable although nearing boiling point.

Among the purchases I'd made in Kampala was a miscellaneous collection of cutlery and this had lain in a cardboard box on the floor in the back of the car. It was now so hot that you couldn't touch it and our bottles of Pepsicola could only be held in a gloved hand and yet the more-than-mulled contents, although lacking any qualities of refreshment, at least remained wet and flavoursome. At Gulu, where we'd been due at 19-50 hours but arrived two hours early, we found everything in a high state of organization and Provincial Commissioner Bere had detailed one of his staff to meet us and take us to his house where he was bent on providing us with baths and dinner-all of which seemed to us to be an excellent way of spending the two hours we had in hand plus the two and a half hours we had planned to stay in Gulu, anyway, since there was no object in arriving at the Juba Ferry, only 200 miles distant, before it started working at 6 o'clock the following morning.

With so much time in hand we could afford to luxuriate and luxuriate we did-in a big way. Every now and then I found myself feeling ashamed to be enjoying a leisurely social occasion when our high-speed run had only just begun; yet where was the merit in denying ourselves these pleasures, only to sit in the dark on the river bank at Juba, waiting for daylight and the ferry ?

The Commissioner signed our log book certifying our time of arrival and, while we bathed and dined, the car was given the once-over by Pressey of Lucas, and petrol and oil were replenished. I had been warned that the Customs officer in charge at Nimule at the Uganda/Sudan border was not particularly

bright and although he'd been specially instructed to be on the watch for us and hustle us through, he was, in fact, in bed when we arrived and we had to wait quite some time while he dressed to receive us.

The night was very still and the cicadas were chafing themselves into a frenzy. Somewhere in the distance we could hear the rhythmic beat of drums and the chanting of native songs and this, we later discovered, was some kind of a party going on a couple of miles away on the Sudan side of the border.

Here we had to put our watches back one hour for the first time and when at last the Customs officer emerged it was just after 11-30 pm., but it must have seemed much later to him because he greeted us with: " I thought you come 17th! “

Although we had risked outstaying our welcome by our long stop-over at Gulu and had really not hurried much since leaving there, with Jeavons at the wheel we arrived on the east bank of the river at Juba long before it was light and settled down to wait for dawn and the first crossing of the ferry shortly after.

We started out with quite a bit of food on board, including some chickens, but it had been so hot that already most of this was inedible and the chickens had assumed an aroma all their own. I got out of the car and flung one of these into the river. Immediately there was a great commotion and it was obvious that there had been competition among the crocodiles for possession of the titbit.

Ron and I got out a couple of powerful torches and proceeded to throw away all our unpalatable food and watch the swirlings and fronthings which ensued and then we got back into the car in double quick time in case the crocodiles should come soliciting !

It seemed, and in fact was, hours before it grew light and then we discovered that we had quite a severe petrol leak somewhere around the tank and had lost about four gallons while standing there. Later the trouble was found to be nothing worse than a loose drain plug, but it worried us until we knew.

We received a jolt of a different kind when the boat arrived, for it brought with it the first examples we'd seen of the stark-naked Nuer herdsmen of Southern Sudan.

They were all males, and if we found their nudity startling it was not more so than the fact that they were positively ghost-like in appearance, being tremendously tall and skinny while, as if to complete the skeleton-like illusion, they were covered in dust. Apparently white ashes are applied to keep off flies - I should imagine it would be most effective if flies really possess any aesthetic propensities.

Later on, in the town, we saw one native who had henna'd his hair and wore bracelets and anklets and walked with a self-conscious and mincing gait, all of which together with the dust was to us, well-droll. Of course, his marks of distinction may have indicated that he had torn a rhinoceros apart with his bare hands, but somehow we thought otherwise.

I don't know why, but the naked girls and women, of whom we were to see many in the Sudan, never seemed bizarre at all like their menfolk-possibly to us readers of modern magazines they were less strange to our eyes.... With what seemed to be almost deliberate perversity, it was always the most beautiful of these girls who were worst disfigured by tribal markings and scars. The men affected

few of these; their disfigurements were more often gangrenous sores on their stick-like legs left by their ornamental metal rings.

Surprisingly, the men were more graceful in their movements than the women and despite their apparent frailty, they are immensely strong and absolutely without fear of physical pain. In Juba we were received right royally and refuelled and dealt with the Sudan Customs formalities as swiftly as possible,

and it was here that the Governor of Equatoria granted me a permit to carry and procured for us on loan a .303 rifle (with fifteen rounds) which was to be handed in on our arrival at Malakal on the far side of the jungle, through which we were about to pass, where it was considered too dangerous for us to go unarmed.

It was in Juba, too, that we picked up a couple of zamzamiyas, which had been made specially for me. These are canvas water-bottles with glass screw-top spouts and, when carried on the front of the car, they keep their contents miraculously cool in any temperature. We fixed them on to our shovel brackets, high up so as not to impede cooling of the radiator.

At last we re-crossed the river to the east bank and set out on the 350 miles through the game country, after which we should come to the ferry at Khor-Ful-Lu. We had been warned by the Governor's aide not to fire at elephants or rhinos as the likelihood of killing one of these beasts with such a weapon was remote and to wound them would probably be to infuriate them so that they would charge the car, with

disastrous results. In fact we saw neither elephants nor rhinos although we continually encountered traces of them. Nor, and this was surprising, did we encounter any giraffes although they abound in this territory; but we did see a few hartebeest and antelope and a number of lions. All the Sudanese men we saw were armed with spears-but whether they were for self-defence for hunting or merely carried from force of habit we couldn’t tell. But we never needed the rifle because our siren, which had been fitted for just this purpose, scared them off immediately. The nine hours it took us to do this part of the trip were hot and dusty hours. We still couldn't bring to eat anything. In fact, from Gulu until we reached Khartoum forty-one hours later I think none of us had anything more solid than an occasional orange.

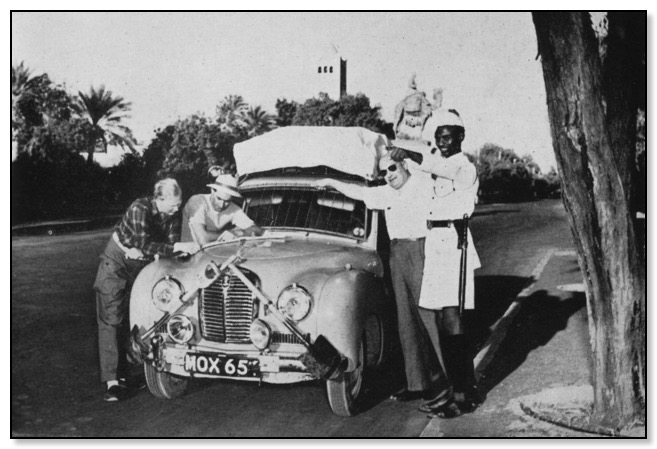

In Khartoum posed with a native policeman

At the tiny and apparently deserted village of Malek, we pulled up momentarily to snap MOX against a background of tuckels. These round, thatched native dwellings, each surmounted by a tuft of straw topping its central pole, have mud walls enclosed in palisades of bamboo.

Even before we'd focused our cameras, the place was seething with life. The villagers came running out to us, waving and shouting, led by an Amazonian creature of colossal-proportions, her hair ochre-dyed carroty-red, her manner embarrassingly cordial.

Men, women, children, dogs, they swarmed everywhere; their excited jabber filled the air and then, simultaneously, as if at a pre-arranged signal, they all started to beg yes, even one of the dogs !

Not knowing what to give them, we leapt aboard the car and made a snappy get-away. But we felt it was a thoroughly bad show and we'd done nothing to improve relations between the Nuers and the white men.

By the time the Khor-Ful-Lu ferry was reached we were very thirsty and felt indescribably scruffy.

I’d been told we should have to hoot on arrival at the ferry in order to bring it across from its moorings. There was no need for this, however, because a little crowd of Europeans were waiting for us on the far bank and immediately we came sight they sent the ferry over to fetch us, a couple of the men from the reception party coming with it-one of whom, Kenneth Snelson of the Jonglei Investigation team at Malakal, wrote to me on our return to England saying, " It is as well that you didn't plan the trip for a few days later, for then the first rains turned the Bor-Malakal-Paloich road into an impassable sea of mud."

On this actual ferry crossing joy was brought to us by Snelson and his companion assuring us that the river water was perfectly safe to drink and getting a member of the crew to bring us some in a bowl. It was nectar and having drunk our fill all three of us took off our shoes and socks, rolled up our trousers and dabbled our feet in the delicious river and scooped up the water in our hands and let it run over our heads and bodies. I doubt whether any of us will forget the liquid delights of that brief crossing of the Sobat.

From the opposite bank it was a run of only 18 miles to the Sudan Airways station at Malakal where we were due to refuel and where our champagne awaited us-laid on, I hasten to add, for its reviving qualities alone, for as yet we'd nothing to celebrate.

It was there all right, but although we had been looking forward to it with the keenest anticipation, when it actually confronted us somehow the idea seemed to have dwindled. Ken, I believe, didn't have any at all and Ron and I had only half a glass each, leaving something more than three bottles behind for the very large crowd which had assembled to wish us luck to drink a toast to our trip instead. It was just getting dark as we left Malakal and I handed over to Wharton who was now driving while I rested in the

back of the car. I dozed and awoke when we pulled up, because the nearside hub bearing was giving trouble and it was decided to change it.

I got out of the car to lend a hand and immediately made the shaming discovery that I was going to be a dead loss because my half glass of champagne, taken on an empty stomach, had reduced me to a state where the only constructive thing I was capable of doing was to steady myself by means of a hand uncertainly grasping one of the struts of the roof rack !

Truth to tell, Ron Jeavons wasn't in much better shape, and Wharton had to change the hub-bearing more or less unaided.

1 decline to admit that our modest indulgence at Malakal may justly be described as an orgy, yet the effects were quite devastating. I don't know about Ron in the navigator's seat, but I can testify to my own relief when Ken had finished the job and I was able once more to recline in the back of the car.

By about 8-30 pm. we had become hopelessly lost-and this nothing to do with the champagne. The trouble was that the trail we were following kept diverging into two tracks and in the dark it was impossible to determine the relative importance of them. We all took spells at the wheel, but even

with both the other two navigating it was still no good.

Plainly one does not motor in the dark in this part of the world unless one has an intimate knowledge of the topography.

Time after time when we came to these diverging tracks we would stop and discuss the pros and cons and would be thankful that we at least had the protection of our car because the night outside was filled with the eerie cries of unidentifiable beasts and birds-although we saw nothing more frightening than a few goats and camels and an occasional lion which was always more scared of our siren than even we three craven travellers could have been of it.

I suppose that the average reader would think that there was great, spine-tingling thrill in being lost in the jungle at midnight knowing oneself to be surrounded by dangerous big game ?

The likelihood of some menacing rhinoceros appearing in one's path; the imminence of trumpeting elephant herds; lions, tigers, giraffes, hartebeests, and so on-to say nothing of sinister snakes slithering towards one-these should have kept us perpetually keyed up and justifiably scared.

The truth is, we were so furiously angry with ourselves for having been so stupid as to get ourselves into our present plight and physically we were so hot, thirsty and weary, that the idea of " sudden death by fang or claw" never preoccupied us at all.

Here we were, three experienced route-finders with upon thousands of miles of world-motoring behind us, inextricably tangled up in a maze of jungle tracks, impotent to find a way out, with the precious hours ticking away inexorably and-and this hurt most of all-with absolutely no one to blame but ourselves !

This, surely, was that bitterest of all pills to swallow-a classic example of over-confidence !

Still, the wild life was all around us; and as time went on a new bother presented itself as we found a tendency to get lost in native villages. Had we been able to see our way, we should not, of course, ever have entered these compounds at all and this only occurred when we followed the less important of diverging trails.

Once in one of these bilad, however, you could drive round and round for ages before finding your way out and as often as not you emerged in the reverse direction along the very path by which you'd entered it.

To be lost in a native village is an exasperating experience. The obviously unaccustomed sound of our car prowling around in the middle of the night did not, surprisingly, produce any signs of life.

Either the natives were too frightened to investigate or else they were sleeping so heavily that they didn't hear us. Personally, I think they were scared for we were making plenty of noise and our headlights must have probed right through the flimsy reed walls of their dwellings. I wonder what they thought we were ?

Anyhow, no one ever appeared, so we blundered on, nosing this way and that, coming time after time to dead ends, turning laboriously or backing; retracing our way and trying an alternative track only to find ourselves confronted yet again by a wall or impassable ditch or just plain bush.

It really was surprising that no one ever came to find out what we were up to. The conviction gradually grew upon me that the occupants of the huts must all be dead. And we felt very nearly dead ourselves.

I had been warned about the difficulties of trying to stick to one's route in the dark on this part of the trip, but, overoptimistic, I'd thought that we were all sufficiently experienced navigators to be able to cope. How wrong I was! We had to rely solely on our compass and as often as not this was little

help because the road on which we found ourselves wasn't running north. Indeed, there were times when we made the mistake of letting the compass decide for us which of two tracks to follow, only to find, a few moments later, that it swung off to east or west and became so narrow that there was no room to turn. And with the sounds we could hear outside, none of us was anxious to get out and explore.

There were two alternatives, either to stop and wait for daylight and trust that this would enable us to get our bearings, or to go floundering on hopefully. The decision was really made for us, for we couldn't afford to waste another seven hours waiting for dawn to break and so we pressed on. Matters were made even worse by the fact that the going deteriorated into a succession of invisible humps and ditches over which we bumped and bounced until we thought the springs must give up at any moment.

On one occasion, when I was at the wheel, we suddenly plunged into a deep pit at something approaching 40 m.p.h. The car stopped abruptly at a giddy angle, we all shot forward in our seats and there was a horrid noise as everything loose in the boot jangled. A shower of dust shot up into the air and there was a sound of glass breaking.

" This time," I thought, " we really have bought it."

Why the suspension withstood a shock like this I shall never know, but inspection showed that damage was confined to the silencer, a dented petrol tank, a shattered water-bottle for the screen-spray, a broken fog lamp glass, an over-rider torn off and a thoroughly chewed up front number plate.

Not without some difficulty, we extricated the car from what now seemed to be an animal trap. Mechanically it was sound in wind and limb and, crestfallen by my exhibition, I meekly handed over the driving to Ken.

But what we didn't know until after daybreak-and this was a tragedy-was that in our crash we had lost both our zamzamiyas before any of us had so much as a sip from them.

We were still by no means sure where we were when it grew light. The only thing I was certain of was that I was glad that I had arranged emergency fuel supplies at Kosti, for we'd done a very considerable unscheduled mileage in going round in circles throughout the night and our petrol was running low. As we went on, tired and thirsty, we were repeatedly bothered by baboons who seemed to be playing that dangerous game of our childhood, " Last Across."

Time after time they would scamper, screaming, over tlit, road almost beneath our front wheels, tearing off into the bush, helter-skelter when we sounded the siren. On one occasion a mother baboon dashed across dragging her small offspring by the hand and I was reminded of the American scientific experiment into the depths of mother-love among these creatures.

A body of naturalists, it appeared, wired up a cell rheostatically with external controls by means of which the temperature of the floor-boards could be controlled. In here they shut a mother baboon with her baby. The scientists peered through peep-holes in the walls all set to record the mother's reactions when the heat was turned on,

As the temperature increased beyond the mildly pleasant, the ape began to caper around with her baby. A few degrees more of heat and she picked up and carried it. Then as the temperature continued to rise she hung the baby around her neck. Still more degrees and she held it above her head. Finally, when the heat became too much, she placed her baby on the floor and stood on it !

Considering the plenitude of big game in that district, it was really extraordinary how few animals we saw, but here and there we did come upon some strange and lovely birds.

We'd been due in Kosti at 2-30 on the morning of Thursday, March 19th, but we were five hours late in getting there, and although our petrol supplies were supposed to be laid on at Rabak Railway Station, shortly before entering the town, there was no sign of anybody when we got there (which, in the circumstances, was hardly surprising) and we carried on along the car-width path over the railway bridge spanning, the White Nile into Kosti itself, with natives driving camels and goats down the steep embankment to enable us to pass.

It was only 7-30 a.m., but already the town was in a bustle. We were lucky to find an important-looking native who understood English and who clambered aboard to conduct us personally to a general store where we replenished our empty flasks and bought biscuits and more oranges.

The storekeeper was a co-operative type and even lent us soap and a towel so that we could wash under a tap in the outside his shop, a procedure which swarms of small

Boys found irresistibly fascinating.

In order to get back on to the road to Khartoum we had to recross the bridge and when we reached Rabak Station on our return, there were our emergency fuel supplies presided over by Sheikh Ahmed Kuku, who assured us that he had there ever since midnight the night before so that how we could have missed each other on that narrow path an hour earlier remains something of a mystery.

By the time we'd refuelled and got under way again we were six hours late and from Kosti to Khartoum is Some 250 miles. Had we been on schedule we should have been due in Khartoum one hour later-from all of which it will be seen that I had allowed seven hours for this part of the journey.

In fact it took all of that because we ran into our first deep sand at about high noon not far from where we could see Ed Ducim in the distance on the west bank of the Nile and on our side of the river there was an unaccountable of thousands upon thousands of camels.

This was the first time we'd been halted by sand and the first time we were to put our sand-tracks and shovels into use.

Lack of previous experience, plus the fact that we were tired, thirsty; and pretty empty, made the job perhaps unnecessarily difficult by comparison with later efforts.

While we were digging and lifting and pushing, a speck appeared far away along the track by which we'd come and this rapidly materialized into a jeep which stopped when it it reached us.

Pest Control had written to me before we left to say that one of their representatives, a Mr. Schmidt, would meet us it Kosti, but we'd seen no sign of him and by a coincidence here was now with two natives aboard on their way to Geteina. He'd not received the message to meet us in time to do so, but he and his companions arrived at the ideal moment from our point of view and with their help M0X656 was quickly restored to relatively firm going and we were on our way once more.

The unexpected appearance of Schmidt had for me an unreal quality which reminded me rather of that succession of fortunate coincidences which having been strung together

was published under the title, " The Swiss Family Robinson." This classic, I have always maintained, is one of the most demoralizing books for children ever written because it creates the misleading impression that the Almighty may always be relied upon to hand one a coconut or a banana just when it is most needed-and by creating this illusion the book discourages personal endeavour.

The sun grew hotter every minute and our exertions in the sand had left us more than somewhat spent physically and Khartoum seemed to be the City of the Never Never. But

even Khartoum could not elude us for all time and at 3.15 we arrived there-still six hours behind our schedule and utterly parched as for some hours we'd had nothing left to drink.

If I were to mention all the many people who befriended us and helped us throughout our journey this book would read rather like a telephone directory, but I must place on record the great hospitality and help we received in Khartoum from Mr. Caldwell, Austin's Sudan distributor and from Mrs. Caldwell.

I must admit I was a bit shaken at first when Caldwell refused to let us just refuel and push on. He said the way from Khartoum to Berber, 250 miles further on, where we